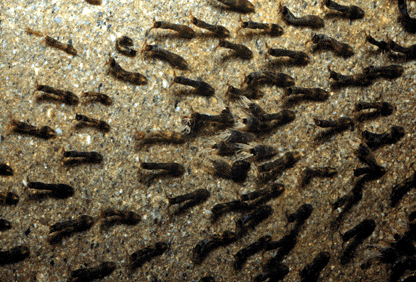

Black Flies (Simuliidae) are speedy black gnats that attack in mobs. They are completely black in color and have a distinctly hunched thorax. There are over 2,000 species of black fly worldwide with over 200 species in the United States alone. Black flies are sometimes mistaken for “eyeball gnats” (Liohippelates--a late spring/ summer species of annoying gnat which licks the eye mucus of animals but doesn’t bite) and other small, non-biting flies that tend to congregate in large numbers in the spring (mayflies for instance) but aren’t attracted to human beings. Season and Habitat Black Flies only breed in fast-flowing water (they love mountain streams); their larvae attach to rocks and filter feed on algae and bacteria. The adults emerge from the water in the spring. Since spring is relative to elevation as well as latitude, “black fly season” in the northeast may end in the lowlands just as it is beginning on the peaks. Dry spring weather will knock populations down; wet springs will bring them out with a vengeance. Most black fly populations are done by mid-July even at the highest elevations. Occasionally, in the late summer, if conditions are sufficiently wet, a few black flies may return, but these are usually short-lived, localized outbreaks. Black flies are intolerant of polluted waters, so a robust black fly population can be a good indicator of a healthy aquatic habitat. Many animals feed on black flies including various bird species, other insects (like dragonflies), fish, (especially trout), and amphibians. Ecology and Behavior Male and female black flies feed on plant nectars, not blood. Only the female black fly will bite for blood: she does so to procure nutrients for egg production. Although black flies aren’t known to be a host to pathogens in the northeast United States, they do leave painful, itchy, and lingering welts. Unlike mosquitos-- connoisseurs who delicately drill into their hosts-- black flies are butchers; they gouge a tiny hole in the skin with their knife-like mouthparts, apply an anticoagulant saliva, and then lick up the blood. They prefer to bite high but will go low often enough to keep you guessing—I’ve found black flies biting between my sandaled toes from time to time. Black flies have acute senses for detecting hosts from a distance but they tend to be somewhat more attracted to darker clothing (which more closely resembles animal fur). When black flies are in full swing they can assault you in such numbers to make you want to jump off a cliff. They tend to fly around annoyingly for quite a while, landing briefly again and again before they settle down to bite. This is a successful tactic (and possibly a genetically coded behavior--one shared by other species of biting flies): the more you aggravate the victim, tickling their skin and making them fruitlessly swat around, the harder it is for the victim to notice when and where the fly lands and bites. Black flies are masters at finding the tiniest patch of skin unprotected by bug repellent—you could take a bath in bug repellent and a black fly will still find that one spot you missed or rubbed it off. They will crawl into your clothing around cuffs to bite beneath. Even when they are not biting, they will get in your eyes, mouth, and ears and will tickle your skin. Black fly bites itch maddeningly, which benefits the black fly population as a whole --itched wounds will bleed and become desensitized to biting, making it easier for other black flies to procure blood from you. Thwarting Black Flies Bug repellent is a must during black fly season (take it with you, as it will wear off when you sweat); I don’t find much difference between manufactured chemical repellents (DEET, Picaridin), or natural repellents (such as lemon-Eucalyptus concoctions, etc.) but I do find that I have to apply a lot of it to discourage black flies and re-apply it during the hike when I sweat it off. I apply it to all areas of exposed skin (except around my eyes, lips, and nostrils), on my hat, and around my collar and cuffs. Even this will not stop them from flying annoyingly around my head. I always wear a hat or keep handy a bandanna to cover my head, and I keep a mesh head net in my pack for the worse black fly days. Black flies are good enough reason to avoid some places altogether in the spring (in the arctic and subarctic spring they can be numerous enough to be life-threatening), but you can pick your days carefully: cold weather or a stiff wind will thwart them (but as soon as you take shelter from the wind, they will be waiting there for you). Black flies are active only during the day and will avoid dark places—you can take refuge from them in the back of a lean-to, an overhang cave, or even a dense thicket of evergreens. They will mob you most when you are taking a break, and they tend to loiter in places where hikers congregate. The longer you stop, the more black flies will find you. Keeping up a good hiking pace can reduce biting—although black flies are fast, a moving target is harder for them to zero in on. When resting, I’ve sometimes succeeded in diverting some of their mob by placing my sweaty backpack as a scent decoy a few feet away from me and watching while they fruitlessly attack it. When camping, the smoke from a fire can discourage black flies (in old time outdoors language, lighting a fire for this purpose is called "smudging"). Because you will not be able to avoid getting bit by black flies if you hike in the northeast in the spring, it’s helpful to have a salve of some kind to coat your black fly bites and keep the itching down.

1 Comment

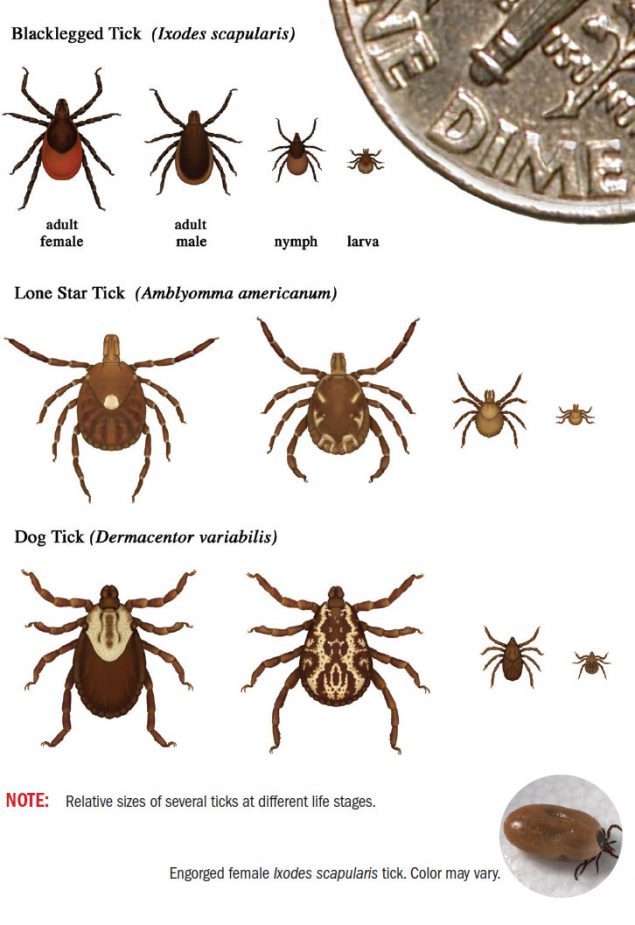

TICKS Ticks (Ixodida) have eight legs and are closely related to spiders and scorpions. Few blood suckers inspire as much loathing as a tick—find just one crawling on you and you’ll be paranoid of every little itch. There is something inherently insidious and creepy about ticks, not the least of which is their ability to harbor and spread debilitating diseases—Lyme Disease, Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis, Ehrlichiosis, etc. Lyme Disease is particularly harsh; combating it can require several rounds of powerful antibiotics. Failing to treat it early can cause acute lifelong symptoms. Lyme Disease is spread primarily by the Deer Tick also called the Black-Legged Tick (Ixodes scapularis), which is common in lower-elevation forests, fields, and shrubland across the Northeast. They are rare to non-existent in higher elevation boreal forests of northern New England. These ticks, identifiable by their reddish lower abdomens, come in a variety of sizes ranging from pencil-eraser-sized adults to pencil-dot larvae. All sizes will bite.

Other ticks: Lone Star Ticks (Amblyomma americanum), formerly a Midwestern and Southern tick, have been expanding their range with climate change and are now occasionally found in southern New England. Like Deer Ticks, Lone Start Ticks are vectors for many pathogens. They can be identified by the single white dot on their carapace. Asian Longhorned Ticks (Haemaphysalis longicornisare) are an invasive tick species from Asia that has been reported in parts of the United States (CT and NY in the northeast); they are less likely to bite human beings, but can transmit pathogens when they do. Winter Ticks (Dermacentor albipictus) inhabit the northeast but they almost exclusively host on hooved animals and are not known to feast on human beings. Winter ticks may infest moose in such great numbers that they can kill the animal. Season and Habitat: Ticks are particularly abundant in the spring, rare by mid-summer, and resurge in the fall. They can linger into winter in snow-free areas and emerge on thaw days. They like damp conditions—drought will force them into hiding. Ticks prefer grassy or shrubby areas; the action of an animal passing through dense vegetation makes it easier for a tick to attach to a host. They are therefore uncommon in woodlands with a clear understory, or on farmland where crops are grown and harvested before the ticks can complete their lifecycle. If you stay on trails (and don’t have a free-range tick-magnet dog with you), you’re a lot less likely to pick up ticks simply because the odds are against it: the entire tick population is spread out among many hikers, dogs and animals passing down the same linear corridor of trail. I rarely pick up ticks on popular, well-manicured trails but sometimes pick them up on seldom used, brushy, or poorly trimmed trails. Ecology and Behavior: Ticks procure blood as food and to produce eggs. They gorge themselves on blood, drop off, then molt or lay eggs. One tick can lay from several hundred to several thousand eggs. The ticks hatch, climb up a blade of grass or low shrub, and wait for a host to pass by. Contrary to folklore, they don’t climb trees and drop on people—doing so would be a waste of the tick’s energy. When they sense the host animal approaching, they reach out with their clingy limbs to hitch a ride on the lower parts of an animal. Sometimes many ticks from the same egg mass will climb the same bit of vegetation—if you’ve picked up a number of ticks over a short period of time this may be the cause. Ticks have acute senses and will sometimes notice and crawl toward a nearby stationary host. Once attached, in order to avoid being dislodged, the tick will usually hunker down and cling tightly with its mouth (not biting) and all eight legs until the host slows its pace or stops to rest. In my experience with dog ticks and deer ticks, the ticks will rarely bite the feet or lower legs. Instead, they will climb to the groin, torso, or head—places where the blood flow is rich and strong. This may be a survival strategy—animals are more likely to notice and chew off ticks clinging to legs and other accessible body parts. Deer tick larvae are somewhat more likely to bite lower—although even they will usually crawl up at least as far as the thighs. Ticks have a flat shape and hard carapace, which makes it difficult to remove or crush them (they can be crushed—between fingernails, or with a rock, car-key, or coin, but you have to work at it). They can survive months without feasting, as long as conditions are not too dry or too cold. They tend to linger where they are dislodged: I’ve found them waiting in my car headrest or steering wheel in the morning, where they crawled astray after I picked them up the day before, and I’ve found them lurking in my shower after dislodging them while cleaning up. Thwarting ticks: The best defense against ticks is to keep them off you, or remove them before they settle in. Contrary to popular advice, I don’t find wearing long pants to be a particularly good defense against ticks. Ticks cling more readily to fabric, less readily to skin, and I’m much more likely to feel or notice a tick crawling up my bare leg than I am to notice one crawling up my pant leg (where it will find its way to my head, burrow into my hair, and become harder to find and remove). Since the tick is usually aiming for at least my groin before it bites, I have a good chance of noticing it on my bare leg before it does any harm. When wearing pants (which I do when bushwhacking), a good coating of insect repellent on my footwear, upper socks, skin above my socks, pant legs, and belt-line helps discourage ticks from hitching a ride (I have had equal success with chemical and natural repellents: DEET, Picaridin, Lemon-Eucalyptus concoctions, etc.). If I’m wearing convertible pants with zip-off legs, I will often find ticks stuck under the zipper flap—a useful feature, and a good place to check for ticks. For that same reason, also check under pocket flaps. If your shoelaces are loose, you’re actively trolling for ticks by sending out lines which they can cling to. I tie my shoelaces up into tight knots for that reason. Some people tuck their pants into their socks, which means the ticks are going to have to crawl up to the head (if your shirt is tucked in) before they settle in (and before you feel them crawling on you)—in my mind, a sketchy practice especially if you have thick hair. In addition to insect repellents, I’ve used Permethrin which is an insecticide (not an insect repellent—do not apply it to your skin!), on my clothing, which is supposed to kill ticks on contact, but I’ve had mixed results with it. The most important tick-thwarting strategy is vigilance. When I know I’m hiking in a ticky area in a ticky season, I check my legs and clothing during breaks and before returning to my car (remember: slowing or stopping one’s pace invites ticks to start climbing upward). When I get home, I check inside and outside my clothing and then my full body in a mirror, not forgetting my groin, bellybutton, genitals, armpits, and back. I shower then check again--every little speck of dirt is a suspect tiny deer tick larva. I will sometimes leave my clothing and footwear outside for the night, or throw it in the wash right away. Throwing your clothing in the dryer on an extended warm or hot cycle will desiccate and kill ticks. It is wise to pre-treat your dog for ticks (dogs can contract Lyme Disease, too) but also check your dog before you get into your car and again before you enter your house --dogs are magnets for ticks and can transport them.

It’s important to remove the tick as gently as possible, making sure to get the tick’s tiny head as well as its body—squeezing the tick or stressing it too much can cause it to disgorge saliva-laden pathogens into your bloodstream. The sooner I get the tick off me, the less likely it will have time to infect me with a pathogen. The CDC suggests that a tick needs to be imbedded 36-48 hours before it passes Lyme Disease to its host, but it's wise to get them off long before that. If you do find a tick embedded, and don’t know how long it has been there, consult your primary care physician about preemptive treatment. Pay close attention to any rashes or symptoms of illness over the next few weeks. Getting on treatment sooner than later can prevent debilitating chronic Lyme disease symptoms. BEAR: You were expecting a growl or something? Black bears don’t actually growl you know. MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: They don’t? BEAR: Nope. Sometimes we grunt or moan. We chomp our jaws and clack our teeth together and make a kind of a huffing sound. Sometimes we swat the ground with our paws. Those are the sounds we make when we’re unhappy. When we’re happy, we’re usually pretty quiet. MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: Really, no growling? BEAR: Nope. Dogs growl. Bears—we’re so over that, evolutionarily speaking. Start growling and the next thing you know you’re licking your butt. Would you lick your butt? MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: Ah, no. That would be undignified. BEAR: Well then. MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: And to be clear, you’re a black bear, right? Not a brown bear, not a grizzly bear. BEAR: That’s right. Real-deal Ursus americanus. There aren’t any brown bears—grizzly bears—in eastern North America. MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: Okay, well, we’re here because bear safety is a hot topic on hiking social media pages these days. BEAR: Dude, I know. People love to bring us black bears up on hiking social media—I’m convinced that half of the people who do that are just bored and trolling for reactions. And so many of the people who respond have no idea what they're talking about--they're just repeating bear myths. You know trolling for bear dirt is right up there with trolling on Lil Nas X’s Montero music video. . . MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: You know this? How would you know about social media? BEAR: Popped out of the woods in front of a hiker a few weeks ago and the guy freaked out and dropped his i-phone. MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: You five-fingered a guy’s i-phone? BEAR: That’s five-clawed technically. And no. Some bears will try to get stuff from people by false charging them. Waste of energy if you ask me. Five out of ten people are wusses when it comes to black bears—just walk across the trail twenty feet in front of them and they’ll wet their pants and drop their packs. Thus the new i-phone. Was gonna give it back to the guy but figured I woulda made matters worse if I chased after him with it. . . MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: Okay, so should people be afraid of black bears and run away? BEAR: You’re asking me to give away trade secrets, and you know what they say. . . MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: Yeah, if you tell me then you have to kill me. . . BEAR: . . .EAT you. If I tell you I have to eat you. MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: Right. So would you? BEAR: Dude. You ever heard of a black bear eating a human being? MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: I’m sure it’s happened, no? BEAR: Listen. According to available stats, two people were killed by wild black bears in the northeast in the last 70 years. Last time was 2002, in New Jersey (don't get me started on Jersey bears and their 'tudes). For New England, you have to go back to the 1940s when a bear was "suspected" of killing a guy in Vermont who was hunting bears. Statistically speaking, a person is more likely to drown in their bathtub or die of a dog bite than get killed by a black bear. MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: So, with those odds, I’m probably a heck of a lot more likely to die in a car accident while driving to a trailhead. BEAR: Right. But you’re not afraid to get into your car. Isn't that interesting? MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: Also, I hear that you eat a lot of veggies. . . BEAR: Ruins our image, huh? MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: So what gives? BEAR: Dude, give me a break. We already get no end of crap from you guys—for instance, in Maine over 3,000 of us are shot each year—all in the course of us just minding our own business out in the woods. . . MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: But those are licensed hunters legally hunting. . .um. . .ahem. . . BEAR: . . .and you homo sapiens kill each other too, pretty often actually—last year alone. . . MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: OK, OK. I agree. Too many of us are asshats, it’s absolutely true. So tell me about the chomping of teeth and huffing thing you do—and the false charging—not growling but it does sound scary—can’t blame a person from freaking out when you do that. . . BEAR: Here’s the deal. We know you’re the apex predator on the block. We know you human beings have more than a few screws loose. So we’d just assume not be seen by you. So, most of the time, we hide. And when we don’t hide, we run. . . MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: But sometimes you charge people. BEAR: Yeah, but probably 95% percent of the time we hide or run. . . MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: How come you never hear about bears hiding from people. . . BEAR: If a tree falls in the forest, and no one sees it. . . MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: But you’re so big—how can you hide? BEAR: Hide from you guys? Really? Dude, you’re freaking amateurs. We’re wild animals. We’re well camouflaged to blend with the shadows in the forest. And we can smell and hear you a mile off—hear you even without your stupid bear bells. And did you know that we have a better sense of smell than dogs--five times better than that of a bloodhound in fact? MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: No, I didn’t know that. So OK, 95% of the time you’re hiding or running away, and you can do that because you’re usually aware of us well before we’re aware of you. Let’s talk about the other 5%. BEAR: Yeah, about that. . . MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: That. BEAR: Okay. So—when you do surprise us—which is pretty uncommon—we get freaked out. I mean, you guys are unpredictable and capable of anything. So I bump into one of you guys and I think: is this guy stalking me? Is he packing? Is this the end of me? MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: Oh, come on. BEAR: No, really. Homo Sapiens= apex predator. Your ancestors booted our ancestors out of their caves and started wearing our skins, and it’s gone downhill from there. You still hunt us. Nothing has changed—and no, don’t get me started on that Uncle Tom of a bear with the stupid hat that you guys use on the trail kiosk posters, give me a break. So you freak us out, and in a close call the only thing we can think to do is to encourage you to back off before you get any ideas about skinning and eating us-- MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: I suppose that’s fair. But it’s still a pretty freaky experience, out in the woods. So tell us how we can all get along. . . BEAR: Well, for starters, don’t make things worse. Don’t be a dick. We’re already scared, so don’t yell and scream at us, throw things at us, wave hiking poles at us. . .don’t do things that make you appear more unpredictable to us than you already are. If you act like a maniac, can you blame us if we assume you’re going to attack us? All bets are off if you escalate the confrontation. MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: OK, I get it, don’t escalate an already bad situation by carrying on like a crazy person. . . BEAR: And—dude!-- don’t run away. MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: Why don’t run away? BEAR: Because it implies you have a guilty conscience and really were messing with us. And that can tempt us to chase you, so that you’ll be even more scared and will tell all your asshat friends not to ever **ck with us bears again. It’s like, “Yeah, YEAH? You want some of this? Huh? You wanna mess with the bears? See what you get when you mess with the bears, hummie? See?!” MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: So what should we do? BEAR: Abide, dude, abide. Have an ordinary conversation with us. Say Excuse me, bear—you know, show some manners. Be as calm as you can and talk as calmly as you can. Eventually we’ll be able to tell you’re chill and want to be left alone, too. Could take up to five minutes—but that’s one of the most exciting five minutes you’ll ever tell your grandchildren about. Amiright? MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: There’s that. But OK, what about that i-phone. . . BEAR: Er, yeah, well, not all of us are well behaved. Some of us have picked up some bad habits. . . MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: About that. . . BEAR: Always one bad apple in the bunch. . .and you guys always fixate on the bad apples. I mean, have you actually watched your television news lately? MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: OK, good point, train wrecks make good headlines. But trains running smoothly never make the news. BEAR: Right. And bad boy bears make all the headlines. MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: Tell me about these delinquent bears. BEAR: Happens in areas where you guys come to camp a lot. Happens for different reasons—maybe you guys start providing handouts to bears for the fun of it, so you can take bear selfies even though you know you ought not to, or it happens because you carelessly and routinely leave your food around where we can find it. Or maybe you guys get freaked out and drop your backpacks when you see us. So we take advantage and pretty soon we learn how easy it is to tweak you into “dropping the cookies.” But it’s like robbing a convenience store, you know? Not exactly grand theft, but if you do it enough you’ll get caught. . . MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: By the rangers? BEAR: Yeah. Caught and shot. Sad. MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: “A fed bear is a dead bear?” BEAR: They say that, but can you blame us for wanting to eat?

MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: So let’s say that a person does everything wrong, and pisses the black bear off, or the bear is a really, really badly behaved bear, and it does attack. Now, you guys outweigh us, you have claws, you’re faster than us, you can swim and climb trees better than us. . . BEAR: Well, don’t play dead—that’s just plain stupid. If another human being were attacking you, would you play dead? Fight back, dude—what have you got to lose? MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: OK, one last scenario. Mother bear and cubs. BEAR: Human mother and toddlers. MOUNTAIN PEOPLE: What? BEAR: Are your mommas any less protecting of their children? Just don’t be foolish. Don’t assume you know the gender of a bear and its maternity status. If you see bears, or bear cubs, and you aren’t in a confrontation with the bear, walk away immediately and keep going. Don’t make a fuss and scream. Don't linger to take photos. Don't try to get a closer look. Just go. If momma gets upset and confronts you, try talking her down. Be calm. Eventually she’ll probably realize you don’t mean any harm, and she and the cubs will go away. She’s more interested in raising her cubs than she is in getting into a tiff with you. She'd rather you were just somewhere else. Think about it. Credits: I inserted good links into the interview to back up the bear's assertions. A lot of this information is supported by the research and experience of bear expert Ben Kilham. Read more about Kilham, his research on bear behavior, his publications, and his non-profit bear cub rehabilitation center in New Hampshire here and here. Consider making a donation to support Ben's work with orphaned bear cubs.

Photos: open source, public domain.

So, I began organizing a hiking series called “Bumps and Falls.” The concept of Bumps and Falls was a simple one: meet in the morning at a designated trailhead, hike a small mountain and/or waterfall, drive to another nearby trailhead, hike a second small mountain and/or waterfall, and so on—until exhaustion or sunset. The logistical beauty of this system was that it allowed participants with different ability levels and time commitments to get some hiking in and enjoy the company of other hikers but bail out at personally tailored junctures during the day—one could hike for as long as one wanted to. The ascetic beauty of it was in getting to hike a lot of really sweet small mountains that one might otherwise overlook, each of which, standing alone, would be an “easy” hike but cobbled together became a moderate to difficult hike (I even ran a waterfall-only version of this group on the hottest days of the summer—we went from waterfall to waterfall and dunked). I do a lot of this kind of hiking when I’m on my own as well, and I’ve come to call it “Cluster Hiking” (or just “Clustering”). Cluster Hiking is a bit different than “Traversing” where one is stringing together a bunch of peaks along a single contiguous foot route with a car spot at either end, but shorter traverses can be included in a Cluster mix. It’s similar, but more buckshot and diverse, to what my friend Michael Blair calls “the Daily Double”—hiking two of the shorter 4,000 footer ascents in the same day—but one can throw a smaller 4K peak into the Cluster mix occasionally. It’s also different than Redlining (now called “Tracing” in certain circles) in that Clustering is destination-specific, not trail-specific—but again, one can Cluster and Redline at the same time. It’s also a bit different than doing a 24-hour Ultra list (for instance, the Saranac Sixer Challenge) in that the focus really is on enjoying the ride and seeing new places—but you could ultra-purpose a cluster if that is the kind of hiking you are into. As a variant of Clustering, sometimes I’ll string together a series of small hikes along a linear travel route from Home to Big Mountain Destination. I made good use of this technique one May while travelling the Skyline Drive and Blue Ridge Parkway to hike in the highlands of North Carolina.

I won’t go into details here—how big or small, or how creatively one Clusters is really a matter of individual preference—and part of the fun in Clustering is in the planning. To plan, one ought to avail oneself of reliable information: print guidebooks and maps, vetted online sources like Trailfinder and Maine Trailfinder (one can use unvetted sources like Alltrails.com—but with unvetted sources there is a certain risk of disappointment and misinformation). For waterfalls, an excellent online source is the World Waterfall Database, with breakdowns by state and GPS coordinates. Below are CalTopo links to some general locations where there is good clustering potential. I hope you enjoy planning and carrying out your next Cluster Hiking experience! --Paul-William The Jackson-Conway area of the White Mountains (NH) The Crawford Notch area of the White Mountains (NH) The Evans Notch area of the White Mountains (NH + ME) The Upper Valley of NH and VT (circa Hanover, NH) The Greater Monadnock Region of NH The Wantastiquet-Pisgah Highlands of NH & the Brattleboro, VT area The Lake Willoughby area of VT The Camden Hills of ME Southern Oxford County, ME The Weld Region of Maine The Moosehead-Katahdin Ironworks Corridor in ME Acadia National Park in ME The Keene Valley region of the Adirondacks (NY) The South Taconic Range & surrounds (southwestern MA, eastern NY, northwest CT) |

TOPICS

All

Humor (The Parsnip)

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed