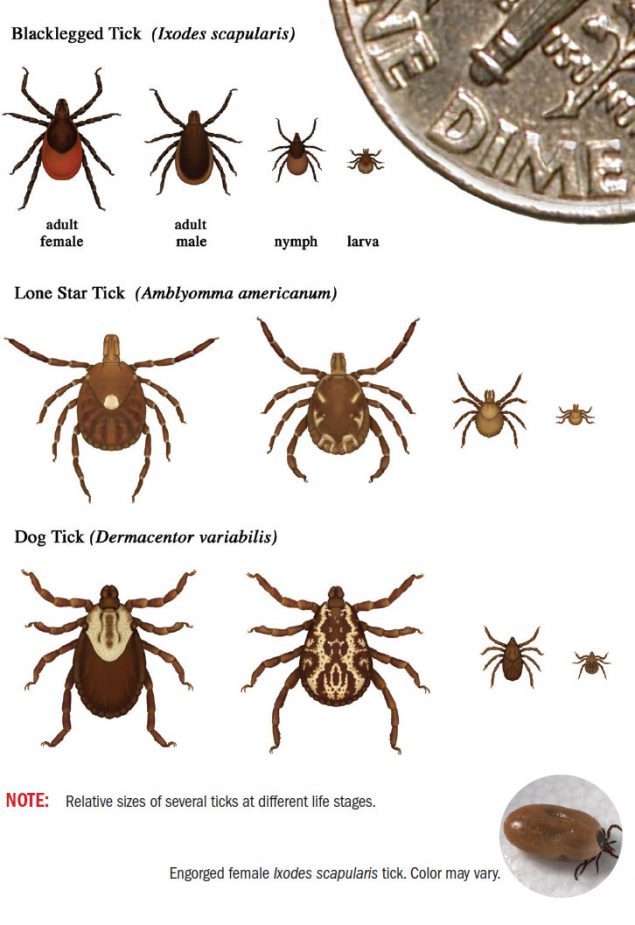

TICKS Ticks (Ixodida) have eight legs and are closely related to spiders and scorpions. Few blood suckers inspire as much loathing as a tick—find just one crawling on you and you’ll be paranoid of every little itch. There is something inherently insidious and creepy about ticks, not the least of which is their ability to harbor and spread debilitating diseases—Lyme Disease, Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis, Ehrlichiosis, etc. Lyme Disease is particularly harsh; combating it can require several rounds of powerful antibiotics. Failing to treat it early can cause acute lifelong symptoms. Lyme Disease is spread primarily by the Deer Tick also called the Black-Legged Tick (Ixodes scapularis), which is common in lower-elevation forests, fields, and shrubland across the Northeast. They are rare to non-existent in higher elevation boreal forests of northern New England. These ticks, identifiable by their reddish lower abdomens, come in a variety of sizes ranging from pencil-eraser-sized adults to pencil-dot larvae. All sizes will bite.

Other ticks: Lone Star Ticks (Amblyomma americanum), formerly a Midwestern and Southern tick, have been expanding their range with climate change and are now occasionally found in southern New England. Like Deer Ticks, Lone Start Ticks are vectors for many pathogens. They can be identified by the single white dot on their carapace. Asian Longhorned Ticks (Haemaphysalis longicornisare) are an invasive tick species from Asia that has been reported in parts of the United States (CT and NY in the northeast); they are less likely to bite human beings, but can transmit pathogens when they do. Winter Ticks (Dermacentor albipictus) inhabit the northeast but they almost exclusively host on hooved animals and are not known to feast on human beings. Winter ticks may infest moose in such great numbers that they can kill the animal. Season and Habitat: Ticks are particularly abundant in the spring, rare by mid-summer, and resurge in the fall. They can linger into winter in snow-free areas and emerge on thaw days. They like damp conditions—drought will force them into hiding. Ticks prefer grassy or shrubby areas; the action of an animal passing through dense vegetation makes it easier for a tick to attach to a host. They are therefore uncommon in woodlands with a clear understory, or on farmland where crops are grown and harvested before the ticks can complete their lifecycle. If you stay on trails (and don’t have a free-range tick-magnet dog with you), you’re a lot less likely to pick up ticks simply because the odds are against it: the entire tick population is spread out among many hikers, dogs and animals passing down the same linear corridor of trail. I rarely pick up ticks on popular, well-manicured trails but sometimes pick them up on seldom used, brushy, or poorly trimmed trails. Ecology and Behavior: Ticks procure blood as food and to produce eggs. They gorge themselves on blood, drop off, then molt or lay eggs. One tick can lay from several hundred to several thousand eggs. The ticks hatch, climb up a blade of grass or low shrub, and wait for a host to pass by. Contrary to folklore, they don’t climb trees and drop on people—doing so would be a waste of the tick’s energy. When they sense the host animal approaching, they reach out with their clingy limbs to hitch a ride on the lower parts of an animal. Sometimes many ticks from the same egg mass will climb the same bit of vegetation—if you’ve picked up a number of ticks over a short period of time this may be the cause. Ticks have acute senses and will sometimes notice and crawl toward a nearby stationary host. Once attached, in order to avoid being dislodged, the tick will usually hunker down and cling tightly with its mouth (not biting) and all eight legs until the host slows its pace or stops to rest. In my experience with dog ticks and deer ticks, the ticks will rarely bite the feet or lower legs. Instead, they will climb to the groin, torso, or head—places where the blood flow is rich and strong. This may be a survival strategy—animals are more likely to notice and chew off ticks clinging to legs and other accessible body parts. Deer tick larvae are somewhat more likely to bite lower—although even they will usually crawl up at least as far as the thighs. Ticks have a flat shape and hard carapace, which makes it difficult to remove or crush them (they can be crushed—between fingernails, or with a rock, car-key, or coin, but you have to work at it). They can survive months without feasting, as long as conditions are not too dry or too cold. They tend to linger where they are dislodged: I’ve found them waiting in my car headrest or steering wheel in the morning, where they crawled astray after I picked them up the day before, and I’ve found them lurking in my shower after dislodging them while cleaning up. Thwarting ticks: The best defense against ticks is to keep them off you, or remove them before they settle in. Contrary to popular advice, I don’t find wearing long pants to be a particularly good defense against ticks. Ticks cling more readily to fabric, less readily to skin, and I’m much more likely to feel or notice a tick crawling up my bare leg than I am to notice one crawling up my pant leg (where it will find its way to my head, burrow into my hair, and become harder to find and remove). Since the tick is usually aiming for at least my groin before it bites, I have a good chance of noticing it on my bare leg before it does any harm. When wearing pants (which I do when bushwhacking), a good coating of insect repellent on my footwear, upper socks, skin above my socks, pant legs, and belt-line helps discourage ticks from hitching a ride (I have had equal success with chemical and natural repellents: DEET, Picaridin, Lemon-Eucalyptus concoctions, etc.). If I’m wearing convertible pants with zip-off legs, I will often find ticks stuck under the zipper flap—a useful feature, and a good place to check for ticks. For that same reason, also check under pocket flaps. If your shoelaces are loose, you’re actively trolling for ticks by sending out lines which they can cling to. I tie my shoelaces up into tight knots for that reason. Some people tuck their pants into their socks, which means the ticks are going to have to crawl up to the head (if your shirt is tucked in) before they settle in (and before you feel them crawling on you)—in my mind, a sketchy practice especially if you have thick hair. In addition to insect repellents, I’ve used Permethrin which is an insecticide (not an insect repellent—do not apply it to your skin!), on my clothing, which is supposed to kill ticks on contact, but I’ve had mixed results with it. The most important tick-thwarting strategy is vigilance. When I know I’m hiking in a ticky area in a ticky season, I check my legs and clothing during breaks and before returning to my car (remember: slowing or stopping one’s pace invites ticks to start climbing upward). When I get home, I check inside and outside my clothing and then my full body in a mirror, not forgetting my groin, bellybutton, genitals, armpits, and back. I shower then check again--every little speck of dirt is a suspect tiny deer tick larva. I will sometimes leave my clothing and footwear outside for the night, or throw it in the wash right away. Throwing your clothing in the dryer on an extended warm or hot cycle will desiccate and kill ticks. It is wise to pre-treat your dog for ticks (dogs can contract Lyme Disease, too) but also check your dog before you get into your car and again before you enter your house --dogs are magnets for ticks and can transport them.

It’s important to remove the tick as gently as possible, making sure to get the tick’s tiny head as well as its body—squeezing the tick or stressing it too much can cause it to disgorge saliva-laden pathogens into your bloodstream. The sooner I get the tick off me, the less likely it will have time to infect me with a pathogen. The CDC suggests that a tick needs to be imbedded 36-48 hours before it passes Lyme Disease to its host, but it's wise to get them off long before that. If you do find a tick embedded, and don’t know how long it has been there, consult your primary care physician about preemptive treatment. Pay close attention to any rashes or symptoms of illness over the next few weeks. Getting on treatment sooner than later can prevent debilitating chronic Lyme disease symptoms.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

TOPICS

All

Humor (The Parsnip)

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed