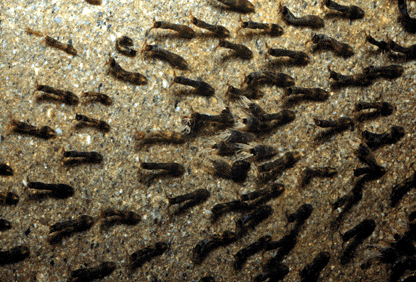

Black Flies (Simuliidae) are speedy black gnats that attack in mobs. They are completely black in color and have a distinctly hunched thorax. There are over 2,000 species of black fly worldwide with over 200 species in the United States alone. Black flies are sometimes mistaken for “eyeball gnats” (Liohippelates--a late spring/ summer species of annoying gnat which licks the eye mucus of animals but doesn’t bite) and other small, non-biting flies that tend to congregate in large numbers in the spring (mayflies for instance) but aren’t attracted to human beings. Season and Habitat Black Flies only breed in fast-flowing water (they love mountain streams); their larvae attach to rocks and filter feed on algae and bacteria. The adults emerge from the water in the spring. Since spring is relative to elevation as well as latitude, “black fly season” in the northeast may end in the lowlands just as it is beginning on the peaks. Dry spring weather will knock populations down; wet springs will bring them out with a vengeance. Most black fly populations are done by mid-July even at the highest elevations. Occasionally, in the late summer, if conditions are sufficiently wet, a few black flies may return, but these are usually short-lived, localized outbreaks. Black flies are intolerant of polluted waters, so a robust black fly population can be a good indicator of a healthy aquatic habitat. Many animals feed on black flies including various bird species, other insects (like dragonflies), fish, (especially trout), and amphibians. Ecology and Behavior Male and female black flies feed on plant nectars, not blood. Only the female black fly will bite for blood: she does so to procure nutrients for egg production. Although black flies aren’t known to be a host to pathogens in the northeast United States, they do leave painful, itchy, and lingering welts. Unlike mosquitos-- connoisseurs who delicately drill into their hosts-- black flies are butchers; they gouge a tiny hole in the skin with their knife-like mouthparts, apply an anticoagulant saliva, and then lick up the blood. They prefer to bite high but will go low often enough to keep you guessing—I’ve found black flies biting between my sandaled toes from time to time. Black flies have acute senses for detecting hosts from a distance but they tend to be somewhat more attracted to darker clothing (which more closely resembles animal fur). When black flies are in full swing they can assault you in such numbers to make you want to jump off a cliff. They tend to fly around annoyingly for quite a while, landing briefly again and again before they settle down to bite. This is a successful tactic (and possibly a genetically coded behavior--one shared by other species of biting flies): the more you aggravate the victim, tickling their skin and making them fruitlessly swat around, the harder it is for the victim to notice when and where the fly lands and bites. Black flies are masters at finding the tiniest patch of skin unprotected by bug repellent—you could take a bath in bug repellent and a black fly will still find that one spot you missed or rubbed it off. They will crawl into your clothing around cuffs to bite beneath. Even when they are not biting, they will get in your eyes, mouth, and ears and will tickle your skin. Black fly bites itch maddeningly, which benefits the black fly population as a whole --itched wounds will bleed and become desensitized to biting, making it easier for other black flies to procure blood from you. Thwarting Black Flies Bug repellent is a must during black fly season (take it with you, as it will wear off when you sweat); I don’t find much difference between manufactured chemical repellents (DEET, Picaridin), or natural repellents (such as lemon-Eucalyptus concoctions, etc.) but I do find that I have to apply a lot of it to discourage black flies and re-apply it during the hike when I sweat it off. I apply it to all areas of exposed skin (except around my eyes, lips, and nostrils), on my hat, and around my collar and cuffs. Even this will not stop them from flying annoyingly around my head. I always wear a hat or keep handy a bandanna to cover my head, and I keep a mesh head net in my pack for the worse black fly days. Black flies are good enough reason to avoid some places altogether in the spring (in the arctic and subarctic spring they can be numerous enough to be life-threatening), but you can pick your days carefully: cold weather or a stiff wind will thwart them (but as soon as you take shelter from the wind, they will be waiting there for you). Black flies are active only during the day and will avoid dark places—you can take refuge from them in the back of a lean-to, an overhang cave, or even a dense thicket of evergreens. They will mob you most when you are taking a break, and they tend to loiter in places where hikers congregate. The longer you stop, the more black flies will find you. Keeping up a good hiking pace can reduce biting—although black flies are fast, a moving target is harder for them to zero in on. When resting, I’ve sometimes succeeded in diverting some of their mob by placing my sweaty backpack as a scent decoy a few feet away from me and watching while they fruitlessly attack it. When camping, the smoke from a fire can discourage black flies (in old time outdoors language, lighting a fire for this purpose is called "smudging"). Because you will not be able to avoid getting bit by black flies if you hike in the northeast in the spring, it’s helpful to have a salve of some kind to coat your black fly bites and keep the itching down.

1 Comment

Roger

8/6/2022 04:09:08 pm

Have you encountered a unique type of biting fly in Mt Donaldson? Not a black fly, stable fly or deer fly. Smaller than a stable fly, bigger than a black fly; it can hover, and crawls under clothing. Very long lasting itchy bite.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

TOPICS

All

Humor (The Parsnip)

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed