|

Although we say mountains belong to the country, actually, they belong to those that love them— Dōgen. Hikers from “out west” who visit New England will often scoff at what we call mountains here. It’s an understandable presumption—after all, our highest peak (Mt. Washington) tops out at 6,288 feet—a mere foothill when compared to the Cascade Range of the Pacific Northwest, with its many peaks above 9,000 feet, culminating in 14,411-foot glacier-bound Mt. Rainier. But that arrogance can easily be dispelled with a hike up our Mt. Washington in wintertime—where the meteorological brutality frequently matches that of the Himalaya, the Antarctic, or a Category 5 hurricane. A good winter ass-whipping and turn-around at the measly treeline of 4,500 feet can’t help but make a person wonder exactly what qualities are prerequisite to the term mountain. In the northeast United States, the term mountain is applied quite liberally without much consideration to elevation. So, for instance, in the lower Connecticut River Valley of New England, in the Metacomet Ridge landform (a layer of volcanic strata tilted upward to form a line of cliffs extending from Long Island Sound to Greenfield, Massachusetts) there are many named “mountains.” The highest “peak” in the range is 1,202-foot Mt. Tom in Holyoke, Massachusetts; the lowest, Saltonstall Mountain in Branford, Connecticut, is only 320 feet high. But the Ridge and its peaks exist in stark contrast to the relatively flat valley of the Connecticut River (>60 feet above sea level in MA, lower in CT). The sharp and imposing cliff faces of the Ridge, up to 100 feet high, are a formidable visual and physical mountainous barrier. On the Metacomet Ridge there are also plenty of peaks called hill that are equally rugged but higher and more imposing than Saltonstall Mountain. Connecticut’s Hanging Hills for instance (high point 1,024’) —to further confound consistency-- contain two prominences called “peaks” and two more called “mountain.” The Hills present a massive, cliffy wall when viewed from the city of Meriden.

The famed mountains of Acadia National Park in Downeast Maine reach only as high as 1,527 feet (on Cadillac Mountain) but when viewed from a ship or nearby island, rise out of the sea so impressively they seem like the Himalaya. And yet early European explorers of New England routinely called the much higher White Mountains of New Hampshire, the White Hills. Distilling from the above, one could say that perspective and topographic contrast might be two relative prerequisites for calling something a mountain, while elevation itself is mostly meaningless. The whole tally of mountain-prerequisites might include:

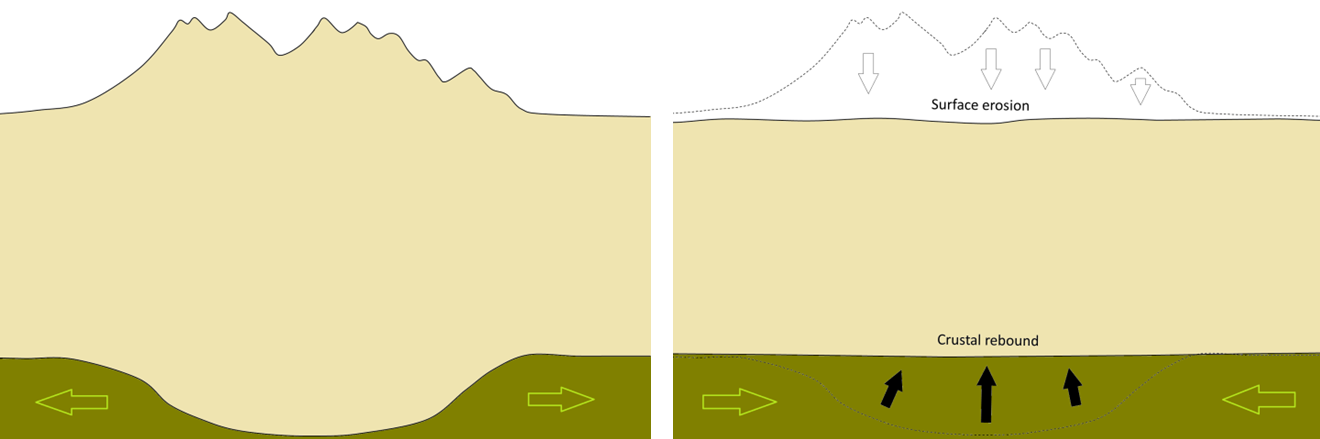

What about earth science? To geologists, mountain and hill aren't scientific terms. Mountains and hills are elevated landforms, and elevated landforms arise from a wide variety of geologic forces. Volcanoes and continental collisions are obvious causes, but erosion and isostacy (land rising or sinking by way of weight and pressure differences in the earth’s crust and mantle) are also responsible. Erosion can create “mountains” by gouging out a flat plateau (the origin of the Catskill Mountains); isostacy in cooperation with erosion can raise “mountains” like magic from a pancake-flat plain. For instance, the Appalachian Mountains were ground down to sea level more than once, then rose up again—go back 100 million years and the location on the continental plate where Mt. Washington now exits was the floor of a valley, and the location of Pinkham Notch was a hill above it. To a geologist, what laypeople call mountain is just another chunk of crustal rock subjected to the contortions and abrasions of our planet Earth. If science is no help, what about language? The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines mountain as “a landmass that projects conspicuously above its surroundings and is higher than a hill.” For contrast (and with a bit of circular logic), it defines hill as “a usually rounded natural elevation of land lower than a mountain.” Similarly, the Cambridge Dictionary defines mountain as “a raised part of the earth's surface, much larger than a hill, the top of which might be covered in snow” and hill as “an area of land that is higher than the surrounding land.” So, per dictionary, the only real difference between a hill and a mountain is a matter of elevation contrast: a mountain offers a lot of topographic contrast, a hill not so much. The word mountain is itself derived from the Old French montaigne, which is in turn derived from the Latin word mons, which essentially meant the same thing to the Romans as mountain means to us—including all the ambiguity. But, interestingly, mons is derived from the Proto-Indo-European “mnā-” which means “to think.” The evolution of language is based on such extrapolations: new things and concepts that are intuitively relatable to the familiar start out with hand-me-down names. We continue to do this today: for instance root is the subterranean part of the plant from which the rest of the plant seems to arise; we use that same word to associate conceptual origins: the root of all evil, the root of the matter. We haven’t yet evolved a new word for this nuanced construction in English. Maybe it was the same for the linguistic root mnā- as it related to mountains. As the ancient ancestors of human beings evolved, they moved from the trees, to the forest floor, to the plains, and, last of all, to the mountains (and the sea). The mountains and the sea were the last external frontiers of humanity, two great forces of nature that were inarguably much larger than us, frightening abodes of gods, devils, and elemental forces that could not be tamed. The mind has always been the last internal frontier. One can look at mountains from afar but to actually go into the mountains requires some courage and some tolerance of risk and the unknown, a willingness to expand one’s consciousness through uncertainty and danger. To risk not-being. To think is likewise a practice and expansion of stark contrast and risk; from the plain of unthinking (the animal mind) rise thoughts which challenge an existence based on simple urges. Thoughts are potentially as dangerous as they are rewarding; they are massive and contrasting when compared to thoughtlessness and instinct; they potentially have no end, and what ends they have are only available to the curious and risk-taking. And I say, there you have it. There is something conceptually human in the term mountain. To think is to imagine and by imagination conceive ideas; mountains, with all their topographic challenges, inaccessible crags and impassible cliffs, secret valleys and snowy tops, are rightfully objects of our imagination more than they are simple landforms defined by mere elevation. Our mythology and history contain innumerable instances of people going to the mountains to find the divine, themselves, peace, harmony with internal and external nature, freedom, and challenge: all endeavors which involve the use, expansion, ingenuity, or wise management of the human mind. Maybe it is that challenge, an essential part of being human, which stands at the core of the term mountain. --Paul-William

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

TOPICS

All

Humor (The Parsnip)

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed