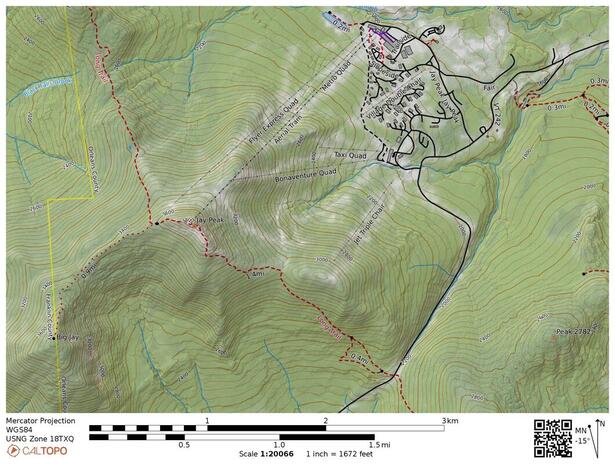

ay Peak & Ski Area. Credit: HanumanIX, public domain ay Peak & Ski Area. Credit: HanumanIX, public domain The Long Trail to Vermont’s Jay Peak (3,858 feet) slabs up the side of the ridge from the trailhead at Jay Pass. It doesn’t go right up the crest of the ridge (which would be the intuitive route), because the Jay Peak Resort ski area occupies the ridge. Some effort was involved in keeping clumsy hikers and graceful skiers apart—it’s harder to build a trail along a side hill slab than it is to build along a ridge; it requires some digging out to keep the footway even, else it would feel like walking in a carnival fun-house. But the vertical real estate slims the higher one goes; ski area and hiking trail begin to bump up against each other. The last stretch, along the exposed summit ridge, closely parallels the course of a wide ski trail blasted out of bedrock; a wooden staircase descends what is left of the natural crown of the mountain. A blocky, industrial-looking summit building squats in another blasted-out nook about 100 feet from the summit. It is only natural to avert one’s eyes and camera and focus on the faraway views instead. As seen from the low rolling farmland to the east, the profile of Jay appears massive, Himalayan even (at least to those who have never seem the Himalaya) because there is simply nothing as big anywhere near it. The ski area on Jay Peak is the northernmost in Vermont, only four miles from the Canadian border. It has the deepest annual snowfall of any ski area in the northeast United States. The vertical plunge is formidable: the four “Face Chutes Route”, with an average slope of 56.5 percent and a maximum slope of 73.9 percent, are the steepest marked ski terrain in the northeast. One of the Chutes even includes a mandatory cliff jump. The hiking route to the summit is easy by contrast: only 1.7 moderately steep miles from the pass trailhead to the summit.  Big Jay as seen from Jay Peak. Credit: Petersent, public domain Big Jay as seen from Jay Peak. Credit: Petersent, public domain Jay has two summits; the second highest is called Big Jay. Like the character Little John in The Adventures of Robin Hood, “Big” is a misnomer; Big Jay is 72 feet shorter than the main summit, Jay Peak. It is broader though, and maybe that is what lends it bigness. Both peaks happen to be among the 100 highest summits in New England, for which there is an official list and a patch for your backpack or jacket if you’re the kind of person to get excited about such things. There is no official trail to Big Jay. Most visitors just stop and gawk from the abrupt rocky crown of Jay Peak without going further. But there is an informal trail-not-a-trail. The route was illegally cut in the late 1990s (allegedly by ski area employees) with no consequences for those involved, an act which may have encouraged a couple of miscreants, in 2007, to boldly chainsaw over 800 trees through pristine state forest land on Big Jay for a downhill ski route. They were found out, thoroughly shamed and punished. But these “trails,” such as they are, linger on. The cut route to the summit of Big Jay is unmarked, brushy, meandering, occluded here and there with rubbery, prickly spruce and fir blowdowns and leandowns—a real rabbit warren of a path, a path that the officials say doesn’t exist, the unofficials can’t maintain, and everyone else mistakenly refers to as a herd path, a term for a path created by repetitive trodding not premeditated hack-and-slash. Although the ridge from Jay Peak to Big Jay is quite narrow, a wooly-wooded knife edge, it is shockingly easy to get sidetracked and headed down the ravine as if there were a disorienting magical force working its will through roots of the mountain. When winter snows bury the evidence of foot traffic, this misdirection is even more pronounced. Even the start of the route is confusing. Northbound off Jay Peak, the Long Trail slips into an unmarked two-foot wide cleft in a ten-foot high snow fence. Viewed from the side, the fence presents an illusion of unbroken continuity. It is not uncommon for hikers to just walk past this junction and continue down the ski trails, or to wander back and forth confusedly. Just beyond the break in the fence, the white rectangular blazes of the Long Trail burn off to the north and the feral path to Big Jay veers westerly along the descending ridgeline. During my December hike the lower parts of the mountain were covered with only a dusting of snow. Heavy rains the week before had melted off the early December snowpack, a la human induced climate change. But the ridge between the summits was playing by different rules and was buried under six inches of snow with frequent two-foot drifts. Luckily, I brought my snowshoes along, always a wise course of action in the winter. This was my third visit to Jay, and my second to Big Jay. I’d forgotten how the ridge messes with your sense of direction, and about the various  At the summit is a small sign with the words Big Jay and an evergreen tree painted on it. Next to it is a glass jar tied to the tree with a piece of string--a recycled jar of marinated artichoke hearts. In the jar is a scrappy notepad and a stubby pencil with which to brag about one’s ascent. I find it fun to imagine a hiker eating a jar of artichoke hearts, rubbing the oil out of the jar with a handkerchief, and tying it to a string—clever improvisation; a touch of humor. Much more character than the PVC cannister registers that are popping up like ugly mushrooms on the most obscure of summits these days. Ritualistically, I always sign these registers where I find them even though I’m skeptical that they are collected and curated in any meaningful way. I suspect that as they become wrinkled, soggy, and mildewy most are simply tossed out and replaced, perhaps reincarnated in a raspberry jam jar next time around. I like them—finding one on a bushwhack summit adds a soft touch of humanity, taking away, if only for a moment, the mountain’s rough edges and pushback: the scratches, the bad humor of trees as they dump snow down the back of your jacket, the do I crawl-under-or-crawl-overs, the leg-sucking spruce traps, the mindgames of losing the route to a wandering moose track then finding the snapped-off branch that gets you found again. The little register wasn’t as comforting to me as a snack bar would be for instance, or a campfire even, but it did make me feel less alone in the wilderness, subliminally: you’ve arrived, cheers, you’re one of us, you made it. I had a bite to eat, wishing I’d brought some artichoke hearts along. I signed the register, screwed the cap of the jar on tight. Then I turned around and contemplated the difficulty of going home.

6 Comments

Michael Blair

1/1/2021 09:23:07 pm

Big doesn't always mean biggest. In this case, it means not the biggest.

Reply

Paul Gagnon

1/2/2021 08:42:15 am

Thanks for clearing that up, lol.

Reply

Inna Radzihovsky

1/2/2021 07:21:05 pm

Beautiful and informative blog. With all your outdoor experience and the wisdom, I am glad you can finally start sharing it with a wider audience.

Reply

Paul Gagnon

1/2/2021 10:30:12 pm

Thank you!

Reply

4/29/2024 12:52:28 am

Your blog is a true gem in the vast landscape of travel content. Thank you for curating such engaging and informative posts that keep us coming back for more inspiration and adventure.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

TOPICS

All

Humor (The Parsnip)

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed