|

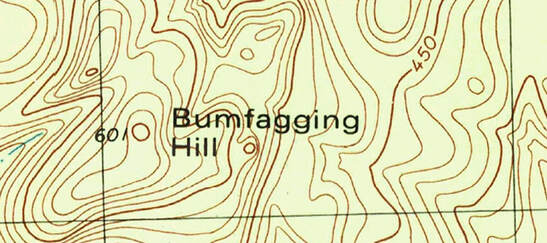

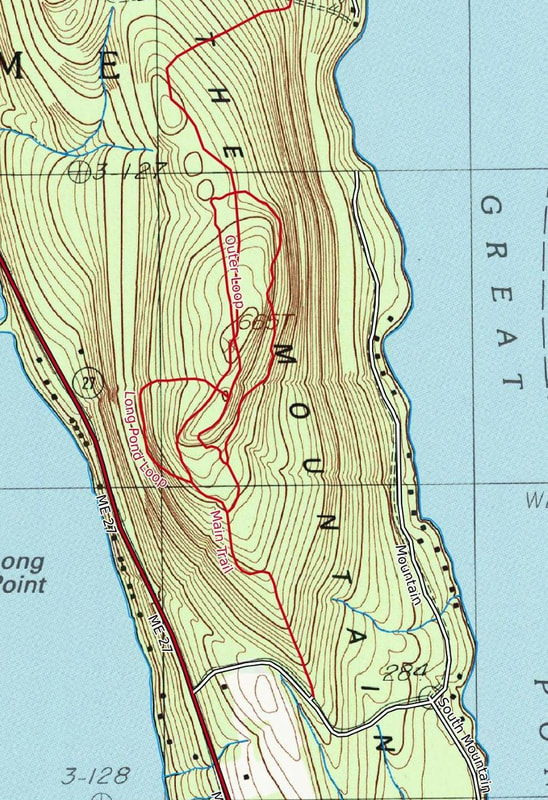

I collect hiking maps and topographic maps. I love looking at them and imagining how the contour lines play out in the physical landscape. As an “off-the-beaten-path” hiker and land conservation professional, this interest serves me well: just a glance at a map will tell me a lot about the terrain I’m planning on visiting. Because I hike and look at maps a lot, I can’t help but wonder about place-names, particularly the designated names of mountains and hills. Which brings me to Bumfagging. Bumfagging Hill, that is—located in Barrington, New Hampshire, elevation 601 feet above sea level.

Such a bureaucracy exists because, if we cannot all agree that a place is called this and not that, then we are going to have a great deal of trouble sharing information and making consistent maps (lacking the affinity of machines who need only numeric coordinates to find meaning in geography). The most important consideration of the USBGN in accepting a place name is demonstrated local use and acceptance of the name. It is the job of the USBGN to determine which local use names are legitimate and which are not. All else being equal, USBGN has tended to favor one name over another based on the relative amount of use: two names enter, one name leaves (but USBGN will preserve historic names that have fallen out of use as “variants”). There are other rules: no features named after living people or commercial enterprises; no derogatory names; and no commemorative names for people who had no relation to the geographic feature. Officially recognized names find their way onto USGS topographic maps and into USGS databases, and from those do Google, Open Street Map (OSM), Rand-McNally, Texico, National Geographic, Garmin, DeLorme and all others rely when making maps and presenting GIS data to the public (OSM does take some liberties there with regard to making up names for topographic features that don’t have official names). Once a name becomes official, it’s not necessarily set in stone—it can be changed if the name falls out of use and another name eclipses it. In some cases the USGBN has rejected government designated names—New Hampshire’s Mount Clay (a sub-peak of Mount Washington) was officially (and oddly) designated by the New Hampshire legislature “Mount Reagan” to elevate Ronald Reagan amongst the godhood of the Founding Fathers venerated in the Presidential Range. But because the USDA-USFS (who owns the mountain in the public trust as National Forest) refused to recognize “Mount Reagan”, because Regan had no real connection to the White Mountains, and because local acceptance of the term was less than tepid, The Gipper will have to go elsewhere for his legacy (stick with airports, old man). MASSA-ADCHU-ES-ET, CHOCORUA, TECUMSEH, and POKE-O-MOONSHINE: SACRED NAMES, APPROPRIATION, WHITEWASHING, AND B.S. Some “local use” place names originated prior to the arrival of Europeans in North America. For Native Americans, naming places was useful in communicating geography and cultural relevance. Places were often named for what they provided (Androscoggin = “place where fish are dried”) or for some physical characteristic (Sebago= “big lake”), and less commonly for a deity or spirit (“Pamola”). Since Native Americans were typically sharing this kind of information on a much smaller scale of geographic reference and awareness than we live today, using the term “Sebago” and “Androscoggin” were meaningful if you lived anywhere in the vicinity of southern Maine where there existed one really “big” lake and a lot of noticeably smaller lakes, or if the best place to dry fish was along a certain river that you happened to live near. Europeans often had ulterior motives in re-using or obliterating native names: to claim the name of a thing or rename it subverts someone else’s association with a thing. When Europeans appropriated Native American places names, they also often butchered the syntax and meaning, or applied them to too broad a geography. For instance, the word Massachusetts is derived from the Algonquin-language phrase “Massa-adchu-es-et” which means “Great Hill”—the sacred landform central to the homeland of the Massachuseuk tribe. The hill is now known as Great Blue Hill of the famed Blue Hills (located near Boston) while the derived spelling Massachusetts has been applied to the entire state. Likewise, Vermont’s Mount Ascutney is a phonetic meandering of the Abenaki Cas-Cad-Nac, meaning “mountain of the rocky summit,” while southwest New Hampshire’s Mount Wantastiquet is closer to the original Wantastekw, which is the Native American name for the Vermont’s West River (which joins the Connecticut River at the mountain’s base) and translates as “lost river, i.e. river on which it is easy to get lost or easy to lose the right trail.” The Uncanoonuc Mountains, two robust, rounded summits just south of Concord, New Hampshire are supposedly a tongue-twisting of the Massachuseuk term kuncannowet for a woman’s breasts (and now you, too, will forever see them that way). New Hampshire’s Wapack Range is a recent portmanteau of two summits with Native American names: Mount Watatic and Pack Monadnock. There are still quite a few mountains and hills in the Northeast bearing true Native American names. Mount Katahdin (ME), Pamola Peak (ME), Mount Agamenticus (ME), Lunksoos Mountain (ME), Mount Wachusett (MA), Pawtuckaway (NH), Mount Waumbek (NH), Mount Monadnock (NH), and Pack Monadnock (NH; pack=”little”) seem to have got their names directly from Native Americans, while Mount Kineo (ME), Schoodic Mountain (ME), Adirondack Mountains (NY), Magalloway Mountain (NH), Mount Pemigiwassett (NH), Shawangunk Ridge (NY), Hoosac Range (MA), Yokun Ridge (MA), and Chickataubut Hill (MA) got their names via white people who associated the topographic feature with certain Native American tribes, individuals, or native-named non-mountainous geographic or naturel features. For instance, Algonquin Mountain and Iroquois Mountain in the Adirondacks are named for high peaks near territorial boundaries of those competing tribes—though Native Americans might have had other names for the peaks. One of my personal favorites is Vermont's Moosilamoo Mountain which means "the moose departs"--what a great visual, but it's not clear Native Americans really applied it to the entire mountain or were just pointing out a moose trail to some misunderstanding white folk.

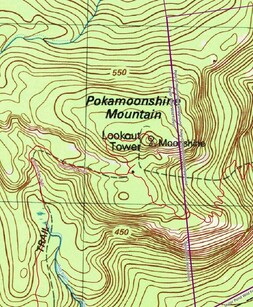

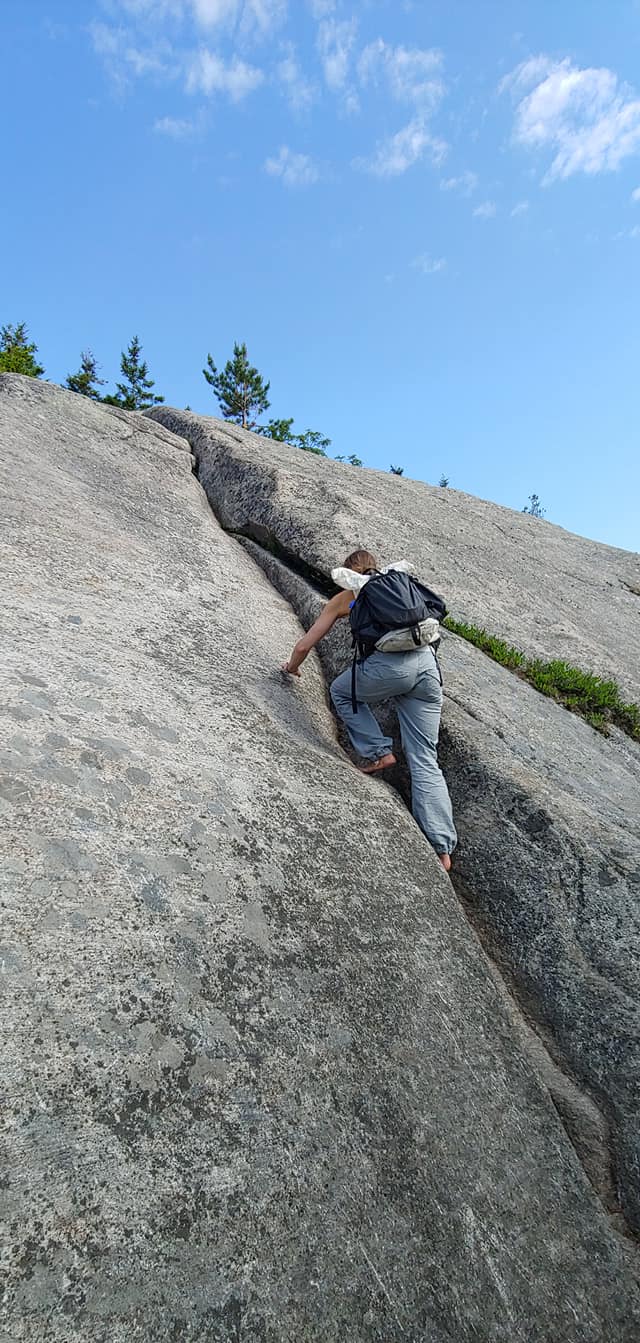

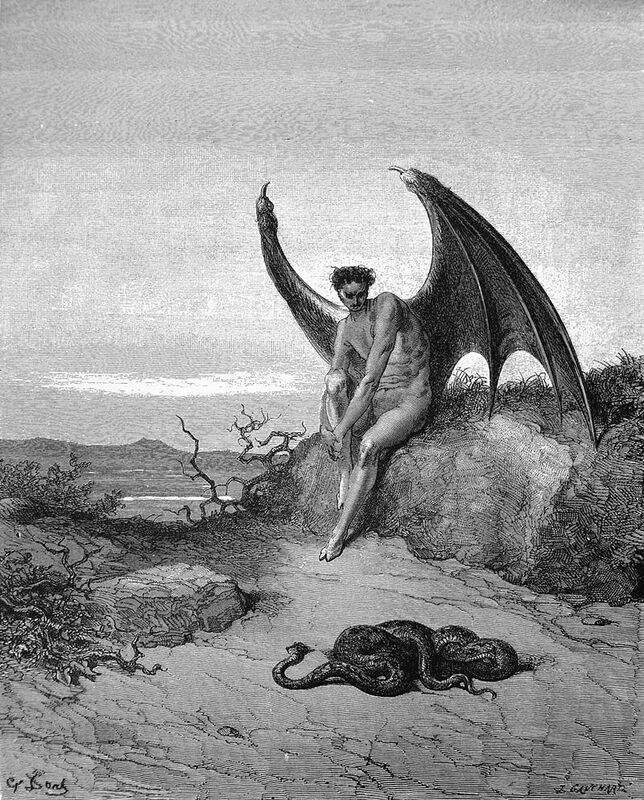

volcanic cliffs that extend from the Holyoke Range in MA south through CT to Long Island Sound at New Haven’s West Rock Ridge). Perhaps the most famous association of an individual Native American to a summit is Mount Chocorua in New Hampshire, the entire mountain a eulogy to cross-cultural dissonance and tragedy. In some cases, the Native American name was abandoned with the meaning partially or wholly retained in English. New Hampshire’s White Mountains were known by Native Americans as Woban-aden-ok: “place of the high white or crystal/mica mountains.” The Sleeping Giant in Connecticut, a volcanic ridge which appears exactly the way it sounds when viewed from a distance, was the mischievous giant and god-spirit Hobbomock, petrified and forced to sleep off his bad behavior after diverting the course of the Connecticut River. Interestingly, Hobbomock is also credited with killing a giant beaver which was terrorizing local tribes in the Connecticut River valley of Massachusetts—you can still see the shape of the petrified giant beaver in the profile of Pocumtuck Ridge (the name of a Native American tribe) and Mount Sugarloaf in that area (curiously, giant beavers with teeth as long as bananas did briefly co-exist with early Native Americans in New England). Other Native American names were applied later by white folk in a fit of historic whitewashing and romatasizing of Native-American and white interactions (sometimes with gross geographic liberties). Examples include Pemetic Mountain (ME), Penobscot Mountain (ME), Mount Norumbega (ME), Mount Norwottuck (MA), Mount Nonotuck (MA), Mount Weetamoo (NH), Mount Kancamagus (NH), Mount Passaconaway (NH), Wonalancet Mountain (NH), and probably Mount Greylock (MA, for the Missisquoi chief Wawanotewat, also known as “Grey Lock”). Mount Osceola (NH) is named for a Florida Seminole chief. Mount Tecumseh (NH) is named after the famous Midwest Shawnee leader and war chief who never set foot in the northeast. Someone (no one seems to be sure who) apparently thought it would be a nice gesture to name a mountain in New Hampshire for Tecumseh after his people were rubbed from the face of Ohio. In some cases the actual connection to Native Americans and Native American usage is frivolous, misused, or questionable. Pocomoonshine or Poke-O-Moonshine is the name of two mountains, one in the Adirondacks and one in Maine (along with a number of ridiculously named summer camps)—a distortion of an Algonquin phrase for something other than bootleg liquor. Legend has it that Quaggy Joe, a small mountain in Aroostook County, Maine (and a state park) got its name from a Native American named “Joe” who was found buried in a tomb near the bog (quagmire= quaggy) at its base. No evidence of any such tomb exists and the name may instead originate from the Maliseet greeting Quaquajo “where are you going?” New Hampshire’s Squam Range gets its name from the lake it its foot, but the original native name of the lake was Keeseenunknipee (“goose lake in the highlands"). For the heck of it, New Hampshirites renamed it another Abenaki name, Asquam (“water”), which was later shortened for convenience to Squam. The Mahoosic Mountains (ME and NH) might be derived from a native term for “pinnacle” or more menacingly (and more fun) “home of the hungry animals”—no one is sure. Perhaps the saddest designation may be the generic Indian (Hill, Mountain, etc.)—where only the vaguest hint Native American heritage remains. Most recently there has been a national trend to re-name mountains (under the USBGN “no derogatory use” principle) that contain the Native American term Squaw, a word with a complicated history which includes derogatory references to native women. For instance, in Maine Big Squaw Mountain and Squaw’s Bosom were officially changed to Big Moose and Moose Bosum. The fact that even Native Americans don’t all agree that “squaw” is a derogatory term ( nevermind that "Moose Bosum" conjures anatomic features straight out of a psychedelic romp through a Hieronymous Bosch painting) suggests that if we’re going to extinguish native-language place-names, then out of respect for Native Americans we at least ought to ask them (in the case of "squaw" ask Native American women) what place-name they’d prefer instead. MOUNTAINS BY IMAGINATION AND PROSPERITY (OR LACK THEREOF) The majority of mountains and hills in the northeast United States were named or renamed by Europeans, rubbing out whatever native place names and meaning might have existed. Like Native Americans, Europeans also frequently named places for how they appeared or what they offered. Probably the most common appearance-themed name for mountains and hills in the northeast is Bald (inc. Baldpate, Baldface, Baldhead, Baldy, Bare, Barren) with over 175 occurrences. Likewise generic are many instances of peaks named Rocky, Stone, Bluff, Cliff, Pinnacle, Peaked, and Round. A local variant of Rocky, particularly common in the Berkshires, is Cobble (ex. Cheshire Cobble and Tyringham Cobble along the A.T., among others) which alludes to cobblestones. Ragged (20 summits) is a frequent name for a mountain or hill with a convoluted ridgeline; Puzzle Mountain (ME) may be the result of a similar observation. Doublehead, Doubletop, Brothers, Two Top, and Twin, are common across the northeast for mountains with two summits, while New Hampshire’s Tripyramid, New York’s Three Brothers, and Connecticut’s Trimountain give praise to peaks of three. Many people are surprised to discover how many Owl’s Heads (24 summits), Saddlebacks (15), Haystacks (27), and Sugarloafs (45) we have. Mountains with rounded tops and facing cliffs from which tufts of trees emerged looked like the heads of owls, and smoothly rounded hills or granite domes with steep sides reminded 19th century Americans of the conical loaf-like form which sugar was purchased and sold back in the day (in Quebec such hills are similarly called Pain de Sucre). Hills or mountains with heap-like shapes looked like haystacks; those with smooth, sloping sags between peaks looked like horse saddles. Also descriptive but less common we have Sawtooth (NY, CT), Knife Edge (ME), and Table (NY, NH). Maine’s well-known 4K Saddleback Mountain has a peak named The Horn, sharpy located along the ridge where a saddle horn ought to be on a saddle. The Beck-horn in the Dix Range of NY reminded guide Old Mountain Phelps of the horn on a blacksmith’s anvil (a beckhorn). Other Horns may have reminded folk of animal horns. Curiously, people saw Sugarloafs everywhere but only one mountain got named Breadloaf (VT)—despite the timelessness of bread to humanity. We have mountains named Fort, Quarry, Monastery, Tower, and Lookout for the structures that do or did stand on them, or for their resemblance to those structures. Lots of mountains were named for their color as they appeared from a distance. Not very Imaginative since most mountains and hills look either Black or (less commonly) Blue at distance; there are dozens of these scattered across the northeast states with Black being among the most common name for a mountain (over 50 references; add Black Cat, Black Bear, etc. and the count approaches 75). Quite a few White (Whitecap, Whiteface, White Cliff, etc), Red, and Green mountains have made the cut. Whiteface usually indicates a big cliff; there are three such mountains (all with trails and cliffs) in New Hampshire and one in New York (one of the 46ers) while those named Whitecap (and Snow) were probably named for their abrupt visibility from a distance in the spring or fall after a dusting of snow. Mountains named Blackcap, Black Snout, or Blackhead (and perhaps Old Speck) probably refer to the dark ring of coniferous forests that crown the summits of those peaks. We also have a Streaked Mountain, a couple Speckled Mountains, and a Rainbow Mountain in Maine where folks couldn’t decide on just one color. The most imaginative use of color is prettily-named Azure Mountain in the Adirondacks. Some mountains were named for mineral resources: we have several Silver (NH, VT, NY, CT), Crystal (NH, ME), Garnet (NH, MA), and one Zircon Mountain (ME); numerous Iron and Lead (for either elemental lead or graphite), and several peaks generically named Mine or Ore. Although we have several summits named Diamond, diamonds are not generally found in the northeast United States and the naming may originate from overly hopeful tales about quartz crystals mistaken for diamonds (as was the case with NH’s Diamond Peaks and RI’s Diamond Hill). In western Massachusetts, Diamond Match Ridge probably refers to the Diamond Match Company, at one time a major New England timber landowner and manufacturer of matchsticks. Auburn, Maine’s Mount Apatite has a substantial old mine containing apatite and many other minerals; the mines are now within a conservation area with hiking trails. Native Americans mined stone for tools on Mount Jasper in Berlin, New Hampshire for which it is now named. Plumbago is another name for graphite, and we have a mountain in the Grafton Notch area of Maine area by the same name. Potash Mountain (NH) alludes to potassium (the shape of the mountain supposedly looks like potash pot--used to derive potassium from burning). In New Hampshire, Isinglass Mountain is named for the pegmatite mines below the peak (the famous Ruggles Mine) which contains a lot of mica, otherwise known as Isinglass. (I should mention that Tinmouth Mountain in Vermont isn’t a pun on orthodontics—it’s a derivation of a traditional Scottish culture name and has nothing to do with tin). There are more Blueberry Mountains (hills, ledges, etc.) in the northeast than you can shake a stick at—many of them actually good berrypicking—but not as many strawberry peaks and none named raspberry (why the hell not? I ask) but we do have a few Cranberries. Trees, too, claim a fair share of peaks. Spruce, Fir (inc. Balsam), Oak, Pine, Poplar, Birch, Beech, Chestnut, and Maple are commonly applied to mountains and hills. Singepole Mountain (ME) probably gets its name for the condition of timber on the mountain following a forest fire. Of the same ilk, we have many Burnt Mountains/Hills and including two creatively characterized Burnt Jackets in Maine (both have trails). Maine has an Onion Mountain--a remote and trailless 3K peak-- one of the few peaks in the northeast named for a root vegetable. Other root names include Potato, Bloodroot, and Gentian--the latter a flavorful wild root and former secret ingredient of Moxie, the classic Maine carbonated beverage and the name of several mountains in the state. “Moxie” is an Mainer-adopted Abenaki term for darkly colored water; it is widely applied to hydrologic features in northern Maine. Then there are peaks named for critters. Certain animal names for peaks presumably came about by appearance (ex. Elephant Cliff in New Hampshire which really does look elephantine) but in many cases it’s a mystery why the name of a common animal (or tree) was applied so specifically (the greater density of squirrels and mice would seem to mean that there should be lots of peaks named for them—but there are only a couple peaks named for small varmints). Including the previously mentioned anatomy of owls we have several whole Owls. Deer (inc. Buck), Bear, Eagle, and Moose are also fairly common but we also have several of Crow, Bird, Raven, Cow, Bull, Elephant, Horse, Trout, Hawk, Snake, Camel, Loon, and Goat. We have Wolves, Panthers (inc. Wildcat, Catamount), and Rattlesnakes, sadly located in places they were extirpated from. Other animal species are named in summits with less frequency. Caribou, for which we have three peaks named in Maine, were once plentiful in northern New England but were extirpated in the 1800s— despite several later attempts to re-introduce them to Baxter State Park (the latest in the 1990s). Our six summits named Black Cat (ME, NY, NH) may be simple dark color references (i.e. Black Mountain) but could refer to legends of melanistic cougars. Blackpoll Mountain in the Berkshires is named for a warbler species. Hedgehog/Porcupine are very common (69 summits) and probably got their names for evergreen saplings poking like quills out of the backs of small, humped peaks. Mosquito Mountain in Maine, despite the pestilential name, is a lovely hike and one of the few honoring invertebrates (others include Caterpillar, Beehive, Beetle, Bug, Bugmouth, and Lobster). Most famously, the name Couching Lion lives on in the USBGN as variant name for Vermont’s Camel’s Hump dating back to the 1600s (“couching” being a heraldic term for a lion in a certain pose). In the Ossipee Range of New Hampshire, Turtleback Mountain lives up to its name with octagonal box-turtle shell patterns in the stone at the domed summit, created by cooling volcanic material. In the Hudson Valley of New York, where the Dutch had an early presence, there are lots of places with Dutch names frequently including the term kill which means creek, from whence the Catskill Mountains get their name, possibly “cat’s creek” because of catamounts—cougars--which inhabited the area. There is also a peak in the Catskills called Bearpen—presumably meaning a place where bears were as plentiful as domestic (“penned”) stock. Famed Goose Eye in the Mahoosic Range of Maine is one of my favorites both in name and character; the name might be a butchering of “Goose High” but who cares—it’s fun. Then there are mountains that got their name in bland gestures of geography; we have multiples of North Mountain, South Mountain, East Mountain, and West Mountain (visualize a local pointing yonder and saying “beyond that thar west mountain . . . “). Similarly, we have several Sunsets and Sunrises, which more cleverly state direction. During a period of firetower construction in Maine in the early 1900s, several as-of-then unnamed peaks were designated with numbers in order to identify their place in the system of fire lookouts; there are still maintained trails leading to the tops of Numbers 4, 5, and 9 Mountains. Other peaks were lazily named for more generally known geographic features that they happened to be near: we have numerous summits named for the towns they are in, or the rivers, lakes, or swamps they are near; we have peaks named “Little” and "Middle" to distinguish them from other peaks nearby (with several glaring elevation mistakes, for instance Big Spruce and the adjacent but higher Little Spruce in the 100 Mile Wilderness of Maine). As the ultimate act of uncreative nomenclature, there is even a mountain in Maine simply called The Mountain. People from that area did not get out often. I’ve always been particularly enamored with mountains named for the furious elements: Lightning Ledge (ME), Thunder Hill (NH), Hurricane Mountain/Hill (NY, NH), Saddleback Wind (ME), Galehead (NH), Firescrew (NH), Storm King (NY), and Mount Aeolus (VT). Also among my favorite names for mountains were those nominated by old-time guides, lumbermen, and hoteliers, creatively or with a grand sense of humor. When famed Adirondacks guide (and likely perv) Orson “Old Mountain” Phelps insisted an ADK high peak retain the local name Nippletop, everyone knew why—and the name stuck despite several attempts to abolish it. At the top of my list are Breakneck Ridge (NY), Ampersand (NY), Wallface (NY), Noonmark (NY), Pitchoff (NY), Scarface (NY), Skylight (NY), Glassface Ledge (ME), Old Speck (ME), Goose Eye (ME), Flying Mountain (ME), Flying Moose Mountain (ME), The Bubbles (ME), Chairback (ME), Ragged Jack (ME), Puzzle Mountain (ME), Rump Mountain (ME), John B. Mountain (ME), Shatterack/Shatterock (MA, VT), Tumbledown (NH and ME, inc. Tumbledown Dick and Tumble Dick), Imp (NH), Black Snout (NH), Thumb Mountain (NH), Cathedral Ledge (NH), Mount Isolation (NH), Crotched Mountain (NH), Bacon Ledge (NH—who doesn’t like bacon?), Mount Deception (NH), Fool Killer (NH), the Hanging Hills (CT), Barn Door Hills (CT), Cathole Mountain (CT), Widow White’s Peak (MA), Gobble Mountain (MA), Poverty Mountain (ME, MA), Equinox Mountain (VT), Romance Mountain (VT), Mount Horrid (VT), Silent Cliff (VT), Grandpa Knob (VT), and the ubiquitous Mount Hunger (ME, NH, VT, NY and MA—lots of people must have starved in those states). In Connecticut, depressives can indoctrinate themselves on Misery Mountain (also peaks in MA, ME, NY), then properly proclaim their suffering by hiking Lamentation Mountain. The term Tumbledown probably alludes to significant rockfall, with the “Dick” added later for humor of one sort or another (possibly an allusion a common old-time pun on Oliver Cromwell’s son Richard’s fall from power in Britain). I’ll leave you to speculate the fun origins of the other peaks mentioned above. DEAD WHITE DUDES A gender-and-ethnic biased mountain of mountains, however, have names either drawn from European geography and culture or for dead white folk, mostly men. In the most innocuous form of the practice (in the days when people were really spread out), a single male-lineage household might be near enough to a peak that folk began to refer to the peak in association with the family name. For example, Smith Mountain (not uncommon) may have got its name because the Smith clan lived nearby. Similarly, we have several Shaker and Quaker summits in the northeast, named for their proximity to those religious communities. Plenty of hills and mountains got their name from Old-World places that sounded pleasant and familiar to colonists, sometimes borrowed from town-names likewise conjured. Old World England place-names abound in the northeast United States along with lesser numbers of French, Dutch, Irish, German, and Scottish names, plenty of biblical names, and even names out of classic literature. In Vermont, Mount Aeolus is fittingly named for the Greek god of the wind. In New Hampshire’s Squam Range we have two facing mountains with names curiously associated with characters in Arthurian legend: Mount Percival (Sir Percival, the protagonist knight who found the Holy Grail) and Mount Morgan (Morgan le Fay, the antagonist sorceress of the Arthurian sagas). Mount Pisgah is the name of at least 25 mountains in the northeast and gets its name for a peak mentioned only briefly in the Old Testament, as does fierce-looking Mount Tekoa which dominates the eastern I-90 gateway to the Berkshires in Massachusetts. Abraham (also Abram) is honored in mountains in Maine and Vermont, and the holy Madonna in Vermont at the Green Mountain crest near Stowe. Perhaps the most common biblical honoree, though, is Satan, who was apparently the consummate hiker. Infernal summits and other geographic features are numerous; summits include Devil’s Den (ME, NH, NY), Devil’s Garden (MA), Devil’s Rock (MA), Devil’s Peak (MA), Devil’s Hill (VT), Devil’s Wall (ME), Devil’s Head (ME), and Devil’s Backbone (ME, NY). There is even a boulder on the Holyoke Range of Massachusetts named Devil’s Football. Presumably these places got their names because of their hatefully rough terrain. Curiously, there aren’t any peaks named “Heaven”, “Jesus”, or “God,” but the French influence in northern areas did result in a few saints squeezing through including St. Regis in NY, St. Catherine in VT, and one oblique Christ reference via St. Sauveur Mountain (Fr. "Holy Savior") in Maine’s Acadia National Park (cross the border into Quebec and every other hill is named for a saint). Lastly, there is a Holy Mount in the Berkshires, where Shakers congregated for rituals, but the list of halos is short overall. Folks did manage to think of quite a few mountains as at least Pleasant (over 30 summits) or as promising Prospect (over 50) if not holy.  The Mansfield Profile (Jared C. Benedict ) In terms of naming peaks for specific individuals, some were christened as a matter of colonial land appropriation for the English lord or financier who funded or supported a settlement, or the crown-designated governor. When residents of what is now Guilford, VT were required to set aside a portion of land in their community for the colonial governor, they happily surrendered the most inhospitable and worthless terrain they knew of and (in typical laconic Vermont humor that persists to this day) referred to it as Governor’s Mountain. Mount Mansfield, the high point of Vermont, is presumed to be named after a land grant by the same name (which was never incorporated as a town) which in turn is probably named in a fit of cronyism for the English magistrate Lord Mansfield who adjudicated in favor of expanding the territory of the same colonial governor who named the land grant “Mansfield” (that said, in a grand coincidence the mountain displays the distinct profile of a man’s face when viewed from the east with Forehead, Chin, Nose and Adams Apple on the map). And then there are the honors, some of them grand, some quaint, and some ludicrous, many of beautifying politicians and military officers. Dismissing both the native names (Agiocochook, Woban-aden-ok) and various local European names for the high peaks of the White Mountains, giddy early explorers, like bulls in China shops, took it upon themselves to declare the highest ground there for United States presidents and other political luminaries. It began with Mount Washington in 1784 (five years before Washington was even elected President let alone dead) and the rest fell like dominoes: Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Pierce, Lincoln, and Garfield. Eisenhower was added in 1972 (Ike had no connection to New Hampshire’s mountains but you can thank and blame him for access to and overcrowding of the Whites through his work in creating the U.S. interstate highway system). Only Franklin Pierce, who was from New Hampshire, had any substantive connection to the White Mountains (George Washington did not sleep anywhere near Mount Washington). The French general Lafayette, who selflessly served America during the Revolutionary War, also got a high peak, while Benjamin Franklin, the scientist of the Founders, only deserved a sub-peak of Mt. Monroe. Mount Jackson is frequently mistaken as one of the peaks named for dead presidents, but in fact the mountain is named for an early New England geologist, not President Andrew Jackson. Vermont, not to be outdone, named themselves a few presidents in the Green Mountains: Roosevelt, Grant, Cleveland, and Wilson. For New York’s highest summit, the wonderful Native American name Tahawus (“Cloud-Splitter”—beat that!) was ignored in favor of Marcy, the New York governor who commissioned the first environmental survey of the Adirondacks and helped set the great Adirondack Park ball rolling. Other peaks of northeast were named for those people who explored, worked, wrote of, and researched the mountains: botanists, surveyors, geologists, guides, conservationists, timber barons, and writers. At least these geographic honors had some legitimacy: Mount Crawford in New Hampshire was named for the pioneer hotelier and hiking guide Ethan Allen Crawford who built what is now the oldest continuously maintained mountain hiking trail in the United States. Starr King, whose fun-sounding name graces a sub-peak of Mount Waumbek, was a popular orator, writer, and Universalist minister who wrote glowingly about the White Mountains. Famous New Hampshirite politician and orator Daniel Webster has several mountains in the state named for him. Mount Marshall of the Adirondacks is named for Bob Marshall, the great wilderness conservationist and the first person to hike to the summits of the ADK High Peaks (along with his brother and a family friend). There are several summits named for New England rural poet Robert Frost but none named for Henry David Thoreau (despite the fact he was an avid explorer of New England mountains himself) though he does get a lookout named for him on Mount Monadnock and USBGN recognizes Thoreau as a variant name of Katahdin’s South Peak (a crag on the Knife Edge). Ralph Waldo Emerson at least got a few hills named for him. Old Mountain Phelps got a mountain named after him in the Adirondacks, more for his colorful personality than his guide skills. Thankfully Maine’s highest mountain, the incomparable Katahdin, retained its storied native name, with just the peak designated in honor of the philanthropist and conservationist Percival Baxter. Baxter had a great sense of humility, and it is good to see that incorporated into his legacy, though he might have even balked at the liberty of naming the high point in his name. Similarly, the high peak of Maine’s Bigelow Mountain got named in honor of Appalachian Trail proponent Myron Avery while the common name was retained for the whole. The Green Mountain Club of Vermont managed to get several Long Trail luminaries recognized in peaks: Battell Mountain, Buchannon Mountain, and Domey’s Dome. Sometimes the designation is undeserved. Famed Ethan Allen (not to be confused with Ethan Allen Crawford) of Vermont’s guerilla Green Mountain Boys, despite being a celebrated war hero, was reputedly a real-estate swindling prick and egoist most of his life; one of the Green Mountains (and numerous other Vermont places), are named after him. Hunter Mountain, the highest peak of the Catskills gets its name from the town of Hunter, which in turn was a renaming of Edwardsville. Colonel Edwards of Edwardsville, who was a disliked tannery owner, was displaced either for an equally disliked former landlord of the area John Hunter, or alternately a town drunk also named John Hunter (possibly an intentional insult to Edwards). Roger’s Ledge in New Hampshire is named for colonial military strategist and genocidal maniac Robert Rogers who led a massacre of women and children in Quebec, burning churches and taking loot (someone really ought to rename that one--though the previous name for the ledge was even worse). Sadly, there are very few summits named for women here in the Northeast. Trail builder and hotelier Kate Sleeper has two peaks (also a ridge and a trail), one of them a New England 100 Highest summit, named for her in New Hampshire. Interestingly, she is one of the few women that gets last name only mention, as is the norm for most peaks named for men (perhaps because women have typically taken on the surnames of men after marriage?). Mount Esther, of the Adirondacks 46, is named for adventurous Esther McComb who may have been the first person to climb the peak—solo, bushwhacking, for nothing but fun, and at the incredible age of 15 (they don’t make kids like they used to). Molly Stark, who has a Green Mountains peak in her name, is widely famous for being the wife of a Revolutionary War general and for doing wifely things, in particular being the silent brunt of her husband’s macho give-me-death-or-give-me-freedom war cry: “. . .or this night Molly Stark sleeps a widow!” Vermont’s 4K Mount Ellen may be named after a fictional character in a book by a male author. Mount Martha (NH), about 3,000 feet lower than lofty Mount Washington, is named for George Washington’s wife Martha. Mount Nancy (NH) is supposedly named for a young woman who died of hypothermia while searching for the lover who spurned her. Maiden Cliff in the Camden Hills of Maine is obliquely memorialized for a woman who also died tragically. No one knows who Mount Olga (VT) and Catherine Mountain (ME; possibly St. Catherine) are named for. Is that all, you ask? Yeah, female representation in topography is a gross injustice of nomenclature. There are a few more smaller hills and peaks also named after women, but the glut of bedrock is testosterone. Something needs to be done about that. Perhaps a shift is coming: in 2014 one of the high peaks of the Dix Range in the Adirondacks was officially named Grace Peak in honor of Grace Leach Hudowalski, a local Adirondacks folklorist, pioneer hiker, and mountain enthusiast (though I’m still curious why Grace and not Grace Leach Hudowalski). TO RENAME OR NOT TO RENAME Most recently, the current superintendent of Baxter State Park publicly suggested that Mount be removed from Katahdin in keeping with the Native American meaning "greatest mountain" (in effect Mount Katahdin really means "greatest mountain mountain"). His case for tweaking the name of Maine's highest summit to eliminate a redundancy in meaning is a good start: there are some really compelling reasons to have a wider conversation about renaming peaks, including equity and inclusion, rethinking names that no longer have any real meaning, and honoring people who have a relevant connection to the geography that will bear their name. (In response to the inevitable cries from traditionalists: it's hard to make a case for traditionalism when the tradition is undeserved or thoughtless). For instance, re-examining Native American legacy in places names puts society squarely in the path of reexamining the long history of broken treaties and genocide perpetrated upon Native Americans by colonials and their heirs. At least we ought do better than the drunken party of surveyors who self-centeredly christened the highest peaks of New England in the name of a bunch of dead presidents that had never even visited the White Mountains. Surely “Cloud Splitter” is a better name for the highest peak in New York than honoring a mediocre, forgotten state governor. Surely we don’t need 45 summits named Sugarloaf. Surely women are no less deserving than men of the honor of having geographic features named for them. On the other hand, there’s something to be said for preserving some of the nomenclature of weirdness we’ve inherited here in the northeast. In Vermont there are a quadro of intriguing mountains in the west-central part of the state curiously tagged The Gallop, The Pattern, The Purchase, and The Scallop--it’s anyone’s guess why, and that kind of quirkiness might mean more for our collective mountain culture than any new name we could conjure up. And having a bunch of summits named in honor of Satan is unavoidably humorous and pokes good fun at the most ridiculous aspects of the northeast’s puritanical past (if we cannot laugh at our traditions, there’s really no hope for our species at all). If we do rename summits, we ought to avoid repeating the follies of past naming practices as they might impose themselves on us through our new technology and culture. For instance, where peaks lack names, peak baggers often apply bland, location-based names, causing those names to stick in the public consciousness: of the increasingly popular New England 100 Highest hiking list, we have the awkward “Peak Above the Nubble” (which is like saying "the peak above the peak") and the redundant “Boundary Peak” (one of a whole string of peaks in Maine with summits directly on the US-Canada border). Worse, the widely available database Open Street Map (OSM) routinely foists some truly heinous name choices upon us through its penchant for automatically naming unnamed summits for pretty much anything that is near them—and their data is disseminated through popular GPS apps worldwide. Too, crowdsource data like those promulgated through OSM are sometimes subject to malicious or vain tweaking—for instance I am aware of one 3K peak in Maine that I’m pretty sure a certain living hiker (or one of the hiker’s friends), named after himself through OSM nutfuckery (and if we keep taking the OSM name for granted eventually it will fall into USBGN "local use"). When we name, let us do so with good intention: be it in tradition, in descriptiveness, in wonder, in humor, or in honor. Our enduring summits—to the extent that we can be so silly to imagine they belong to us—deserve better from us than a Bumfagging.* *The term “fagging” is probably related to the practice of hazing that occurred in English schools circa the 19th century (occasionally including associated sexual exploitation and assault) where underclassmen were forced to run errands and carry baggage for upperclassmen (maybe itself derived from the older meaning of the word fag= sticks bundled in order to carry them from one place to another). The word “bum” has a number of meanings (buttocks, a homeless person, a lazy person, or a “of poor quality, or wrong”); in this case, combined with fagging, it could mean doing a real poor job of serving another person. Geographically: a useless hill.

1 Comment

6/28/2024 08:12:43 am

Exploring the world through your travel blog is like embarking on a thrilling expedition to the heart of adventure. Your tips and recommendations have transformed my trips into memorable escapades filled with breathtaking scenery and cultural discoveries. Each excursion planned using your insightful guidance becomes a seamless voyage of exploration and self-discovery. Your dedication to sharing the best adventure moments through engaging narratives and stunning visuals is truly commendable. Thank you for being a constant source of inspiration and for enriching my travel experiences with your invaluable insights. Your blog has become my trusted companion in discovering new destinations and creating lasting memories.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

TOPICS

All

Humor (The Parsnip)

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed