I ignored the advice, through- hiked the A.T. end-to-end and the leg was fine-- in fact, it was made a lot stronger by the experience. But the knee still troubles me from time to time. It's been a bit of a rollercoaster: some years I don't seem to have much trouble with it, other years I do. Going on thirty years of vigorous hiking since the initial injury, It's held out far better than I'd expected. The injury has changed my hiking over the years: it has slowed me down a bit on the downhill and flats, made me more careful of how I walk, and make me reasonable about the miles (I rarely will do a hike of more than 16 miles in a day). I have also taken up barefoot hiking (long story; fodder for a separate post) which has taken some stress off the knee during hikes (one must step more gently on the downhill when shoeless, which reduces wear and tear on the connective tissue).

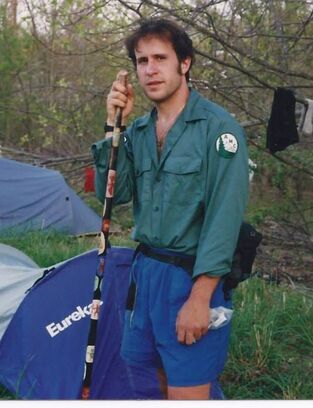

My left knee looks different than my right knee: it is thick with internal scar tissue and musculature which, I imagine, have insulated and buffered it, not unlike how a tree will grow gnarly around an old wound. I imagine that my careful hiking practices and regular strengthening have extended the life of my knee beyond the threatened diagnosis (every doctor that looks at it reminds me what a mess it is). I have not yet submitted to the knife. I rarely wear a brace and I use just one wooden hiking stick for support. But it would be foolish to imagine that knee replacement surgery is not in my future.

The easiest and most common conclusion to that question, post-recovery, is bragging: I survived such-and-such, I’m a such-and-such badass, look at my badassery and tremble. Not to demean the value of celebration or the power of positive thinking, but if that’s your only tack and reward you’ll find plenty of back-pats on social media to help prop it up—you won’t even need to do it yourself; others will be glad to inflate your ego for you and help you dismiss your mortality. Ego-props as an end-goal are cheap prizes, however. It’s like hiking partway up a mountain and turning back, not because the weather is evil and I can’t reasonably go the rest of the way but because I am lacking in a fundamental kind of ummph that has nothing to do with hiking ability or trail conditions. It means I was never forced (or never conceded) to move beyond the denial stage (I’m not subject to the Law of Entropy the way other people are) or the anger stage (I “beat” my injury) before I was fortunate enough to recover. In his book Who Dies? the late Stephen Levine, famous for his series of books on conscious suffering and dying, asks the reader to imagine they are terminally ill, unable to care for themselves in the most basic of ways. Levine poses a series of questions: [paraphrasing here] when you are no longer able to do the things that most defined you, and others have to take care of your most basic needs (on the extreme end: buying your groceries, rolling you around in a wheelchair, bathing you, wiping your ass) what are you? who are you? where is that “I” that you were in previous years: the father, the attorney, the bicyclist, the carpenter, the doctor, the mother, the caregiver, the football player, the rock-climber, the skier. . .the hiker? Along those lines you may ask yourself: Who am “I” when my days of obsessively and relentlessly hiking Ultras and Grids and Redlines are officially over? Who am I when hiking a 4,000-footer is out of reach? Who am I when I can no longer easily walk down a flight of stairs? This line of questioning automatically awakens my old friend Despair—maybe he (or she) is a friend of some of you, too. A few years back I impaled my leg on a sharp tree branch while on a long hike through the Mahoosuc Range (a side bushwhack up the now-appropriately-named “Trident” peak); little bits of wood were imbeded deep in the wound; the wound became infected and I went in for surgery. I thought: what if they can’t fix this? What if I lose my leg? Can I live with that? I won’t sugarcoat it for you: a little, dark piece of the hiker in me was quietly engaging suicide scenarios even before I went in for surgery. I’m not mentioning this to set the stage for judging that kind of thinking. The beloved and brilliant White Mountains author Guy Waterman, who suffered debilitating (albeit hidden), lifelong mental health issues, ended his life by committing intentional hypothermia on Franconia Ridge—for a hiker, quite a way to go out. I cannot know his suffering and so cannot judge it or the outcome he chose. I can only use it as a mirror as I observe my own thoughts during the times I’ve had to question the continued existence of my identity in the face of a contrary or unacceptable reality. Any forced change in one’s self-identification is itself a kind of death. In preparing for "death" the mind grapples with the stages of coping with loss: denial, anger, bargaining, grief, and acceptance. Some of us move through those stages more easily than others; some get stuck. If I can no longer hike big mountains, but can still hike, the “big mountain hiker” must die to make room for a different kind of hiking identity. If I can’t hike anymore but can swim, kayak, bicycle, whatever, then the hiker must die and make room for those new identities. There is a loss and grieving inherent in that even if you work hard at burying the emotional labor—don’t let anyone tell you different. But beyond the endless morphing of identities lies the deeper question: what is this “I” that I keep creating? Is it important? How? When I strip it away, what is beneath it? In terms of hiking, one can ask more focused questions: what exactly IS a hiker? What does it really mean to be a hiker--beyond mere goal-posting and exploration? What is the kernel of that identity—and does it really even exist? I don’t have answers to these questions (and all answers will likely be subjective and privately individual) but I do think it’s important to ask them sooner than later. In some aboriginal cultures there is a practice of “preparing for death” which begins at a young age and continues until the end of biological life. The process, which involves song, vision quests, prayer, and other practices, is really a delving into the question of self-identity and what lies beyond it. As I understand it, if it is done well it can prepare the mind for the “little deaths” of identity that occur throughout life: changes in occupation or role, loss of loved ones, tribal warfare, change of physical ability and mental acuity. And in modern life in America, also divorce, unemployment, foreclosure, empty nests, pet death, failed business ventures, stock market crashes, hospitalizations, breakups, house fires, car accidents. . .and hiking injuries. If I can muster the courage to step beyond the props of the ego, the most important question might not be "when will I recover and hike again?" but "when the hiker can no longer hike [eventually, whether temporarily or more lastingly], what is left? Exactly who is this 'hiker' I have come to imagine I am?" Thanks to those who submitted photos and stories of their injuries. [Photo credits, by name in caption]. Postscript: my recent knee diagnosis is “badly contused ligaments/tendons /patella.” I consider it a deferment.

9 Comments

Michael Blair

3/11/2021 07:43:53 pm

Well done.

Reply

Danny Hughes

3/12/2021 07:00:40 am

Nice writing. Very thought provoking on the 'what if' side of injury. What stuck with me is that you do go through all the phases of grappling with loss, denial, anger, etc. and each phase you have to convince yourself of an alternative path. I call them "your demons" and if you let them they will get the better of you creating doubt and so ultimately it is a mind game to force them out or at least reconcile to wait and see until you pull yourself through a tough time. In the absence of information humans like to conjure their own ghosts. Making lemonade by finding other pursuits while injured helped me find time to cope through uknowns and the uncertainty of injury. It also changed me where I now am more empathetic toward others injuries and help lift their spirits to get through their tough spots. There's always something else to do so tying your identity to one thing is very limiting and while seemingly important ultimately constrains you from being you.

Reply

3/12/2021 12:58:12 pm

This blog floated across my FB page at a time when I have been pondering my own ‘death as a hiker’.

Reply

Conor Rafferty

3/12/2021 08:54:56 pm

Very deep post.

Reply

Paul Gagnon

3/12/2021 09:43:26 pm

Thanks, everyone, for your feedback and great responses!--Paul

Reply

Toolbox

3/13/2021 05:31:49 pm

Doc- my 1st reaction is where is mount agamentus and when can I hike it? I rebound from meniscus tear and appreciate the Phoenix aspect little deaths. Pot holes will be filled and it is not just physical injury that can pause the action but the pressures of fatherhood and feeding the little birds...how can I mantain until a return to the mountains? Steve Toulmin Hanover sspitting distance from AT brings me comfort..

Reply

Paul Gagnon

3/15/2021 08:36:24 pm

Good to hear from another class of '94-er :-)

Reply

3/13/2021 07:17:41 pm

Started to write something and then decided I needed to think about this more. Nice piece though, I appreciate good writing. If you can't hike, you can always write!

Reply

Paul Gagnon

3/15/2021 08:35:36 pm

Thanks, Philip! You were an inspiration in creating this blog.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

TOPICS

All

Humor (The Parsnip)

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed