|

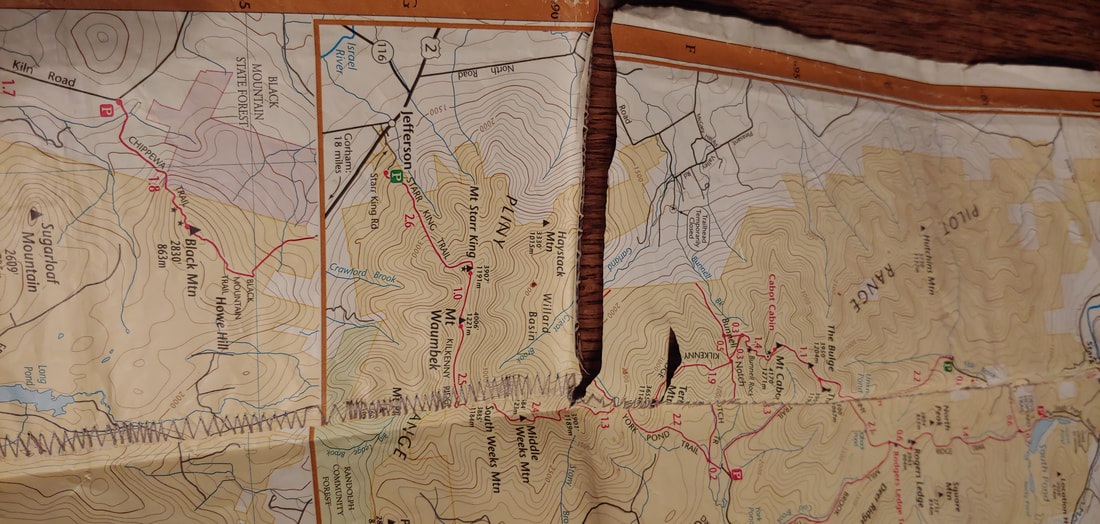

When we think of the classic shape of a mountain--all pointy, barren, and snow capped--there are few peaks in the northeast United States that capture that archetype more than New Hampshire's Mount Chocorua in winter. Chocorua's conical, bald summit (3,490') has been a landmark destination for hikers for over 150 years and figures prominently in the folklore of the White Mountains: the mountain gets its name from the legend of a Native American by the same name who, according to fable, leaped to his death from the summit in culmination of cultural misunderstanding-double revenge- tragedy. Chocorua is one of my favorite peaks: delightfully climby and open; challenging but not an overly long hike--and I like to get to it at least once per year if I can. The mountain is also on the 52 With A View hiking list, which includes the finest sub-4K peaks in New Hampshire. A winter-conditions hike up the mountain seemed like a good fit for my hiking club--Random Group of Hikers--which was gearing up for a return after a long Covid-related hiatus, so I put it on the calendar. We had planned to do a loop starting at the popular Piper Trail from the south, but concerns about post-snowstorm parking area plowing at Piper caused me to change the approach to an OAB via the White Mountain National Forest's Champney Falls Trail from the north (7.6mi RT). The falls, which drop off a ledge into the side of a short slot canyon--are some of the most unique and impressive in the state. We got 5 inches of snow overnight, on top of a layer of black ice: snowshoes were on the menu for the ascent and light traction for descent, but crampons would not have been out of order on the summit cone of the mountain where a few ice bulges made for tricky scrambles. The falls were partially frozen and the four brook crossings unfrozen but manageable on stepping stones. Views from the top were glorious. --Paul-William

0 Comments

Although we say mountains belong to the country, actually, they belong to those that love them— Dōgen. Hikers from “out west” who visit New England will often scoff at what we call mountains here. It’s an understandable presumption—after all, our highest peak (Mt. Washington) tops out at 6,288 feet—a mere foothill when compared to the Cascade Range of the Pacific Northwest, with its many peaks above 9,000 feet, culminating in 14,411-foot glacier-bound Mt. Rainier. But that arrogance can easily be dispelled with a hike up our Mt. Washington in wintertime—where the meteorological brutality frequently matches that of the Himalaya, the Antarctic, or a Category 5 hurricane. A good winter ass-whipping and turn-around at the measly treeline of 4,500 feet can’t help but make a person wonder exactly what qualities are prerequisite to the term mountain. In the northeast United States, the term mountain is applied quite liberally without much consideration to elevation. So, for instance, in the lower Connecticut River Valley of New England, in the Metacomet Ridge landform (a layer of volcanic strata tilted upward to form a line of cliffs extending from Long Island Sound to Greenfield, Massachusetts) there are many named “mountains.” The highest “peak” in the range is 1,202-foot Mt. Tom in Holyoke, Massachusetts; the lowest, Saltonstall Mountain in Branford, Connecticut, is only 320 feet high. But the Ridge and its peaks exist in stark contrast to the relatively flat valley of the Connecticut River (>60 feet above sea level in MA, lower in CT). The sharp and imposing cliff faces of the Ridge, up to 100 feet high, are a formidable visual and physical mountainous barrier. On the Metacomet Ridge there are also plenty of peaks called hill that are equally rugged but higher and more imposing than Saltonstall Mountain. Connecticut’s Hanging Hills for instance (high point 1,024’) —to further confound consistency-- contain two prominences called “peaks” and two more called “mountain.” The Hills present a massive, cliffy wall when viewed from the city of Meriden.

The famed mountains of Acadia National Park in Downeast Maine reach only as high as 1,527 feet (on Cadillac Mountain) but when viewed from a ship or nearby island, rise out of the sea so impressively they seem like the Himalaya. And yet early European explorers of New England routinely called the much higher White Mountains of New Hampshire, the White Hills. Distilling from the above, one could say that perspective and topographic contrast might be two relative prerequisites for calling something a mountain, while elevation itself is mostly meaningless. The whole tally of mountain-prerequisites might include:

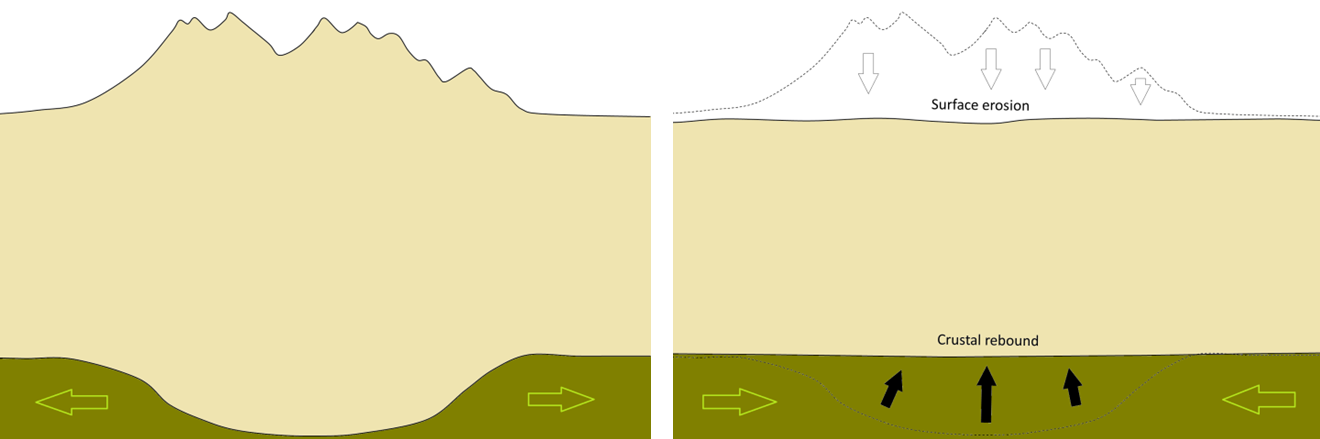

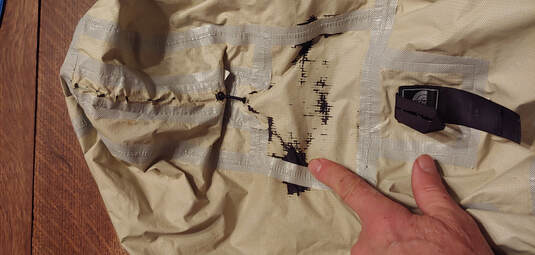

What about earth science? To geologists, mountain and hill aren't scientific terms. Mountains and hills are elevated landforms, and elevated landforms arise from a wide variety of geologic forces. Volcanoes and continental collisions are obvious causes, but erosion and isostacy (land rising or sinking by way of weight and pressure differences in the earth’s crust and mantle) are also responsible. Erosion can create “mountains” by gouging out a flat plateau (the origin of the Catskill Mountains); isostacy in cooperation with erosion can raise “mountains” like magic from a pancake-flat plain. For instance, the Appalachian Mountains were ground down to sea level more than once, then rose up again—go back 100 million years and the location on the continental plate where Mt. Washington now exits was the floor of a valley, and the location of Pinkham Notch was a hill above it. To a geologist, what laypeople call mountain is just another chunk of crustal rock subjected to the contortions and abrasions of our planet Earth. If science is no help, what about language? The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines mountain as “a landmass that projects conspicuously above its surroundings and is higher than a hill.” For contrast (and with a bit of circular logic), it defines hill as “a usually rounded natural elevation of land lower than a mountain.” Similarly, the Cambridge Dictionary defines mountain as “a raised part of the earth's surface, much larger than a hill, the top of which might be covered in snow” and hill as “an area of land that is higher than the surrounding land.” So, per dictionary, the only real difference between a hill and a mountain is a matter of elevation contrast: a mountain offers a lot of topographic contrast, a hill not so much. The word mountain is itself derived from the Old French montaigne, which is in turn derived from the Latin word mons, which essentially meant the same thing to the Romans as mountain means to us—including all the ambiguity. But, interestingly, mons is derived from the Proto-Indo-European “mnā-” which means “to think.” The evolution of language is based on such extrapolations: new things and concepts that are intuitively relatable to the familiar start out with hand-me-down names. We continue to do this today: for instance root is the subterranean part of the plant from which the rest of the plant seems to arise; we use that same word to associate conceptual origins: the root of all evil, the root of the matter. We haven’t yet evolved a new word for this nuanced construction in English. Maybe it was the same for the linguistic root mnā- as it related to mountains. As the ancient ancestors of human beings evolved, they moved from the trees, to the forest floor, to the plains, and, last of all, to the mountains (and the sea). The mountains and the sea were the last external frontiers of humanity, two great forces of nature that were inarguably much larger than us, frightening abodes of gods, devils, and elemental forces that could not be tamed. The mind has always been the last internal frontier. One can look at mountains from afar but to actually go into the mountains requires some courage and some tolerance of risk and the unknown, a willingness to expand one’s consciousness through uncertainty and danger. To risk not-being. To think is likewise a practice and expansion of stark contrast and risk; from the plain of unthinking (the animal mind) rise thoughts which challenge an existence based on simple urges. Thoughts are potentially as dangerous as they are rewarding; they are massive and contrasting when compared to thoughtlessness and instinct; they potentially have no end, and what ends they have are only available to the curious and risk-taking. And I say, there you have it. There is something conceptually human in the term mountain. To think is to imagine and by imagination conceive ideas; mountains, with all their topographic challenges, inaccessible crags and impassible cliffs, secret valleys and snowy tops, are rightfully objects of our imagination more than they are simple landforms defined by mere elevation. Our mythology and history contain innumerable instances of people going to the mountains to find the divine, themselves, peace, harmony with internal and external nature, freedom, and challenge: all endeavors which involve the use, expansion, ingenuity, or wise management of the human mind. Maybe it is that challenge, an essential part of being human, which stands at the core of the term mountain. --Paul-William Although it isn't officially winter until December 21 (winter solstice), the weather gods don't care--they'll gleefully dump snow and freezing temperatures on us any day now (and have already got started in the mountains). Being prepared for safe winter hiking in the mountains of the northeast United States means having winter-worthy gear and a matching attitude. If you're contemplating winter hiking in the mountains for the first time in your life, unless you're a witless person you're probably at least a little anxious about preparation. But even experience doesn't always translate into preparedness: there's a little corner of hell reserved for us old timers called complacency. Whether new and anxious or old and careless, I hope you'll find this bulleted list helpful in your prep for the snow, ice and negative digits. Gear inventory and prep:

Mental and physical preparedness:

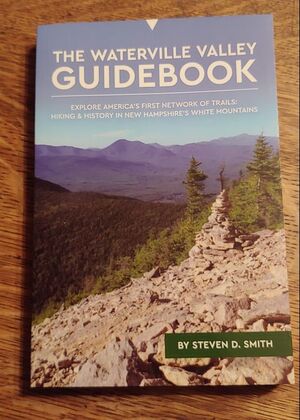

of a peakbagger's bible: The 4000-Footers of White Mountains. Well, Steve has a new book out (as of 2020), this one a treatise on all the trails, mountains, and historic features of the Waterville Valley region of the White Mountains: The Waterville Valley Guidebook (332 pages/ $25). Like The 4,000-Footers, the book is meticulously researched, with tidbits about the history of the area and its hiking and ski trails, local nomenclature, settlement, geology, ecology and all sorts of other fun facts (the scope of the book includes everything from village paths to rugged trails on the nearby high peaks of Osceola, Tecumseh, and the Tripyramids). Unlike The 4,000-Footers, The Waterville Valley Guidebook is loaded with color glossy photographs, some of them current, some some historic. The tone of the book is objective and informative but accessible and laid back. Both an incredibly detailed and entertaining hiking guidebook and a handsome coffee table book, it's the kind of book you'll want to pick up and read just for fun on a rainy day or consult briefly before setting out for an adventure on a sunny day. --Paul-William |

TOPICS

All

Humor (The Parsnip)

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed