|

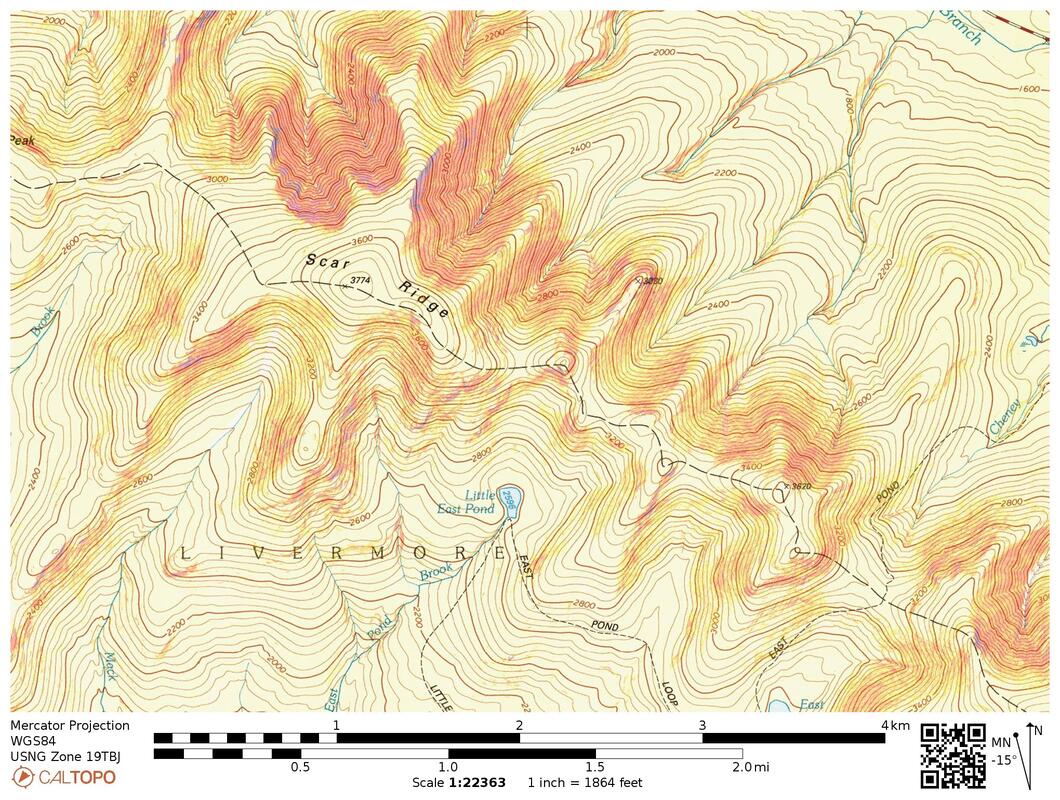

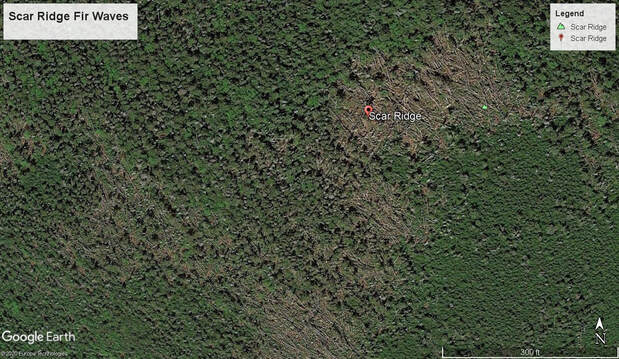

Scar Ridge, 3,774 feet, is probably the most notorious of the New England 100 Highest summits—by reputation a trailless, viewless, devil’s obstacle course of blowdown fir trees, cliffs, and doghair spruce thickets. The bad reputation harks back to the pre-social media/ smartphone GPS era, when people who hiked it relied primarily on map and compass and the war stories hikers told other hikers, word-of-mouth, about their attempts. That reputation has stuck with the mountain over the years, persisting today despite blog posts rife with step-by-step photos, freely shared GPS tracks, a safety-orange PVC summit cannister, a somewhat beaten-out herd path, and (as we found during our recent ascent) plastic flagging tied to trees (more on that later). As is true for any bushwhack, ascent strategy, and the obstacles and opportunities that lie in wait along the chosen route, play a role in determining what species of “fun” one has. There are indeed truly hellish ways to ascend Scar. During our recent trip in December of 2020, we intended to avoid as much hell as possible. But we wanted to hike it in winter which (as you’ll see) added some unusual twists to our strategy. Scar Ridge presents a bold 2.5-mile long east-west skyline, a topographic extension of trail-tamed but higher Mount Osceola to the east from which it is separated by the deep-plunging notch of East Pond-Cheney Brook, a wooly rift scoured out by glacial ice sheets thousands of years ago. To the west of Scar, the ridge drops 1,000 feet then continues as the well-known but lesser summits of the Loon Mountain Ski Area. Another sub-peak, Black Mountain, extends northerly from Scar toward the Kancamagus Highway. Visible from said Highway, and in no small way adding to the scenery of that drive, are a series of precipitous slab-slides which glint icily in the sun—the “Scars” that give the ridge its name and lend it a forbidding aspect. The entire ridgeline is crowned with evergreen balsam fir, a common holiday Christmas tree variety, tame in the home covered with tinsel and ornaments, but when left alone on the mountaintops undergoes a malevolent transformation into tangled chaos. To be fair, tangled is a just complaint but chaos is not—there is a true natural pattern to it called a “fir wave”, and Scar Ridge is one of the finest places in the White Mountains to experience the beauty (and abuse) of such a phenomenon. Fir waves. Close-up view (above) of fir wave on Scar Ridge and (below) on North Brother in Baxter State Park showing the characteristic wave pattern over a broader area. Images © Google Earth What happens in a fir wave is this: as a group of fir trees mature and become higher and heavier, they also become more exposed to the fierce winds that sweep across the mountain tops. The wind desiccates and weakens the trees; eventually the strength of the roots to hold the weight of the trunks against the force of the wind fails, and the trees tumble down like jackstraw dominoes in huge, linear patches in the direction of the prevailing wind. This exposes the next patch of mature trees downwind, and it isn’t long before they start tumbling too. Meanwhile, fir saplings waiting patiently below the canopy, barely eking out inches of growth over decades, suddenly surge up like bean sprouts as the older trees collapse. Fir grows fast when it has sun, and the saplings all mature at nearly the same rate. When they reach too high the process starts all over again. If you were to look at the phenomenon under a time-lapse of centuries it would seem as graceful as a gust of wind blowing through a wheat-field, the wheat flattening, rising, then flattening again. And in aerial imagery of some of New England’s higher peaks, that wave-like pattern does indeed leap out to the naked eye in beautiful ruin.

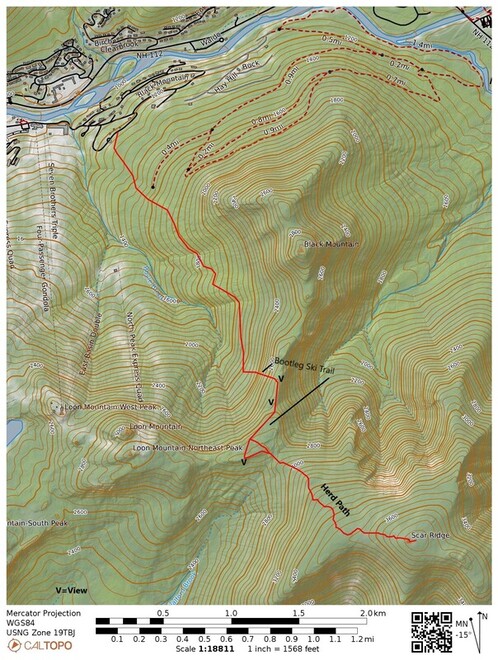

But the ski area has recently tightened its winter “uphill policy”—hiking up the ski slopes costs a thievish $30 dollars per head and you are only allowed to go as far as Loon’s west summit, not all the way to North Peak. You aren’t permitted to hike down either—you either have to ski (lugging your skis up first) or take the lift down (which disqualifies you from earning your New England 100 Highest creds). So we weren’t going via the ski area. The “other sane way” (according to social media this is what most hikers do in winter) is to bushwhack up from the Kancamagus to northeast via the east bowl of Black Mountain through mixed terrain, pick up a bootleg ski trail on the ridge, and then the herd path. The trouble with this route is it involves a major river crossing. The river was high at the time of our hike and not frozen over. So we did something different, using aerial imagery to work it out. I enjoy looking at aerial imagery of trees and trying to read the story their crowns are telling me—a skill I picked up during my career in land conservation, one that, before airplanes and photography, only birds excelled at. Scrutinizing aerial imagery of Scar (courtesy of CalTopo) I could see that the fir waves at the ridgeline look like a box of toothpicks scattered by giants. Active waves were less pronounced on the north and west side of the Scar, and very pronounced on the south and east sides. I could also see that the tree canopy on the west side of Black Mountain (sub-peak of Scar) was mostly deciduous trees with moderate to large crowns—which probably meant open woods and easier walking. And I could see that one could bushwhack in behind the condominiums to the east of the ski area (gaining a little elevation boost at start), slab the bowl the west side of Black Mountain, push through some denser spruce trees at steep terrain just before the ridge, and then pick up the known herd path at the base of Scar. What the aerial imagery didn’t show was the steep bootleg glade ski trail that descends from just south of the Black-Mountain-Scar Ridge col. We bumped into this trail and were able to use to get up a lot faster (I am curious about the history of this trail—if anyone knows, please share). Along the way we got to see an interesting balanced boulder, and we found a nice view of the Scar Ridge’s scars waiting for us at the top of the slope. A little past that is another view looking westerly toward the ski area. Since there was little snow on the ground at the time (most of it had melted off in a big rain storm the week before) we also took a detour at the start of the herd path to a narrow view ledge looking south (another aerial image discovery).

the first visitors to an alien planet. To me, the flagging was another theft of that primal hiking experience, a further taming of what was not meant to be tamed. The last tenth of a mile of herd path meanders through the fir wave at the top of the mountain, a god-fist smashed place it seemed, primitive and ice-agey, inhuman except for the bright orange PVC summit register cannister piggybacking a forlorn tree. It was frozen shut and we could not open it to sign our names. And that didn’t seem wrong.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

TOPICS

All

Humor (The Parsnip)

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed