Summit lists got their start in the northeast United States in 1918 when a young Bob Marshall set out with his brother to climb the 46 highest peaks in New York's Adirondacks; Marshall's proto-list of high peaks became officially known by the 1930s as the Adirondack 46ers. The Appalachian Mountain Club soon followed with its own list of 46 4,000 footers in New Hampshire (now 48 peaks) officially designated a thing in 1957. The AMC's "New England 4,000-Footers" and "New England 100 Highest" lists are just slightly older and incorporate the highest summits in greater northern New England. A few other lists were added in the latter 20th century (notably 52 With A View) but pervasive "list-ism", in terms of raw popularity of the practice, and the proliferation of lists, really didn't take off until the early 21st century. In the northeast we now have lists dedicated to the high peaks of the Catskills above 3,500 feet in elevation (33 summits), the Adirondack Firetower Challenge (for those who like to climb things that sit atop other things), the 52 With A View list (created to honor the wonders of sub-4,000 foot summits in New Hampshire) and the New Hampshire Trailwrights 72 list (which includes mandatory trail work as a requirement--shouldn't they all?). For the OCD-inclined there are now "Grid" lists, which require that you hike each of the peaks in a previously established summit list once in every month of the year. "Gridding" started off with the New Hampshire 4,000 footers and has quickly metastasized to include other lists. Then there is "Redlining", which could more aptly be called "trailbagging" (now called "tracing" in certain circles to differentiate it from the term's superficial resemblance to the completely unrelated but evil economic practice of "Redlining") where you hike all the trails contained within a particular hiking guidebook and highlight them on a map or fill out a spreadsheet to keep track. And there are lots of "off the radar" lists that lack formal recognition (at least for the moment) but which have an increasing base of devotees: county high point lists, town high points lists, range lists, 3,000 footers lists, 2,000 footers lists, etc.

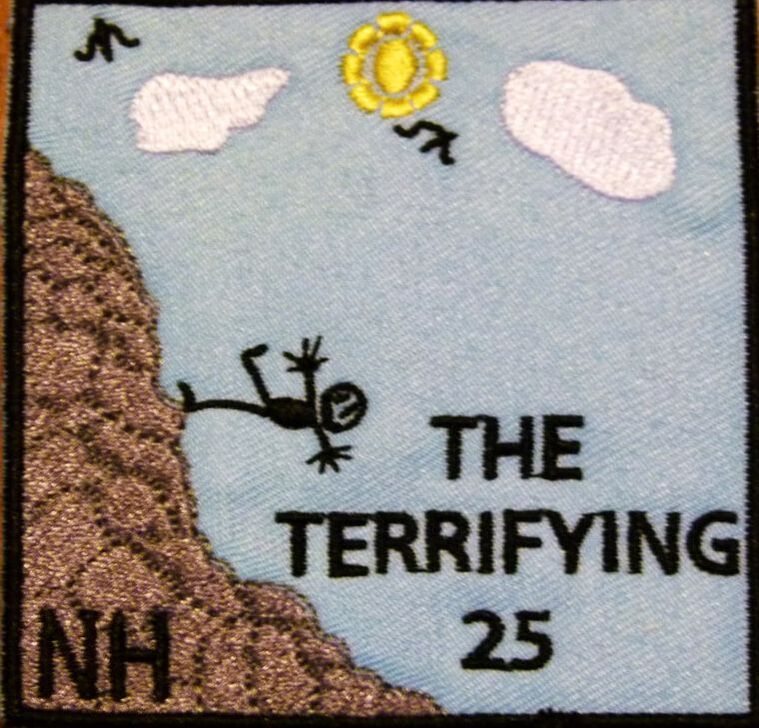

Recent lists of this ilk include the Saranac Six, the Maine 4,000 Footers, the Go North 9ers, the Camden 10, the Forest Society's "Reservation Challenge" --among others. The sadomasochists have also jumped on the bandwagon by grouping several popular high--mileage popular traverses and shorter summit lists into an extreme "ultra" hiking challenge--where you have to do each item within a 24 hour period, hopefully without peeing blood secondary to a NSAID overdose or bonking from electrolyte depletion. The acronym "FKT" (Fastest Known Time) has become popular among those seeking their temporal 5-minutes of fame by doing this or that list in record time over a season, a year, a 24 hour cycle, or whilst hopping on one leg, crawling to the summit, or hiking it all naked or backward-- or whatever else hasn't been done before (I am waiting patiently --no pun intended-- for the pop-culture fad of FKT to fade and the SKT star to rise. In my mind, SKT and "reverse ultras" are a heck of a lot more challenging--go ahead, think through it). On top of all that, there are both official and unofficial winter-season lists of many of the above. Many list officials will also offer you a patch and cert for your dog--as if your dog really cares about hiking patches and you aren't really living vicariously through your dog by it. The listing phenomenon is not limited to New England of course--you can collect lists from other states and foreign nations, and if you add in completion lists for long distance trails (there are ultras rights to those too, where you do more than one in a year) you'll be busy for the next ten reincarnations--provided your karma doesn't favor a return as a domesticated goat. I fully expect these lists to proliferate such to the extent that the gravity of the available patches sewn or glued to your backpack will someday weigh more than the pack itself plus essential contents. Of course you don't need to subscribe to any of these lists to enjoy hiking in all its goodness. And there is nothing stopping you from creating your own, personally meaningful list of destinations. Why be so imposed upon then? My friend John Clark (currently doing the White Mountains Grid) likes to remind me that peakbagging is what motivates him to get out of the bed on weekend mornings. Not a few people I know do need that structure. Others do it for a variety of reasons, some rational and wholesome (comradery among peers, a sense of accomplishment, the psychological reward of closure, or because they already hiked the prettiest mountains, 90% of them happen to be list peaks and why the heck not do the last few) and some questionable (peer pressure, social media smackheadery, anorexia athletica, or failure of imagination). It's the case that people will either evolve or devolve through the experience of hiking: a list itself is a neutral thing (I like to think more hikers tend to evolve than devolve but perusing hiking social media makes makes me doubt in humanity). Given all the lists out there to choose from, and the lack of enough time in your short lifespan (even if you are a trust-funder or couch-surfing dirtbag hiker), it makes sense to choose wisely. One might chose to favor lists that are uncommon or interesting in creative ways (as the original ADK 46er and AMC White Mountains 4,000 footers lists were uniquely so back in the day). In that respect, the Terrifying 25 list (T25) really stands out.

Not only are the trails challenging, they are also some of the most scenic and interesting trails in the White Mountains. Take for instance the Subway--a trail that passes underground through boulder caves, or the Table Rock Trail, with its finger of skinny stone dangling over the remote harrow of Dixville Notch. To get the comical T25 patch you have to hike 20 core trails plus 5 out of 14 "elective" trails on the list. The rest of the rules are clean, no-bullshit: no catering to egos ("Hike this list for fun and adventure, not for record-breaking or bragging rights. . . there won't be any public announcements of who's the youngest, oldest, fastest, slowest, etc. person to finish the list"), no dog patches ("dogs don't care one iota about lists, patches, or any other silly human status marker"), no winter patches (some of the trails are technical ice climbs in winter. . .and the list is intended to be non-technical), and no fuss about how you get to the start of the trail (you could, for instance, drive the Mount Washington Auto Road to get to the top of the trails that originate in the Great Gulf, and hike down from there--"cheating" by most list standards). There is something inherently refreshing about a hiking list that is centered squarely around fun and exploration and which statedly resists being co-opted into a retentive status contest, even as those seeking status will surely collect the patch as a notch-in-the-belt and brag on social media about how badass they were in conquering the Terrifying 25. So be it--you can ask people to be lighthearted but you can't expect it. For myself, just contemplating the silly T25 patch reminds me of how silly and miniscule my own ego ranks in the face of geologic time and the eon-spurning, cloud-crowned mountains: still beautiful, mysterious, demanding, and god-like even after my 30+ years of obsessive hiking. I'm not but a jester dancing at their feet. Given that hiking lists are popular and will continue to proliferate, I propose that we come up with more fun lists like the Terrifying 25. Consider it a challenge: enter your proposals in the comments below. --Paul-William

4 Comments

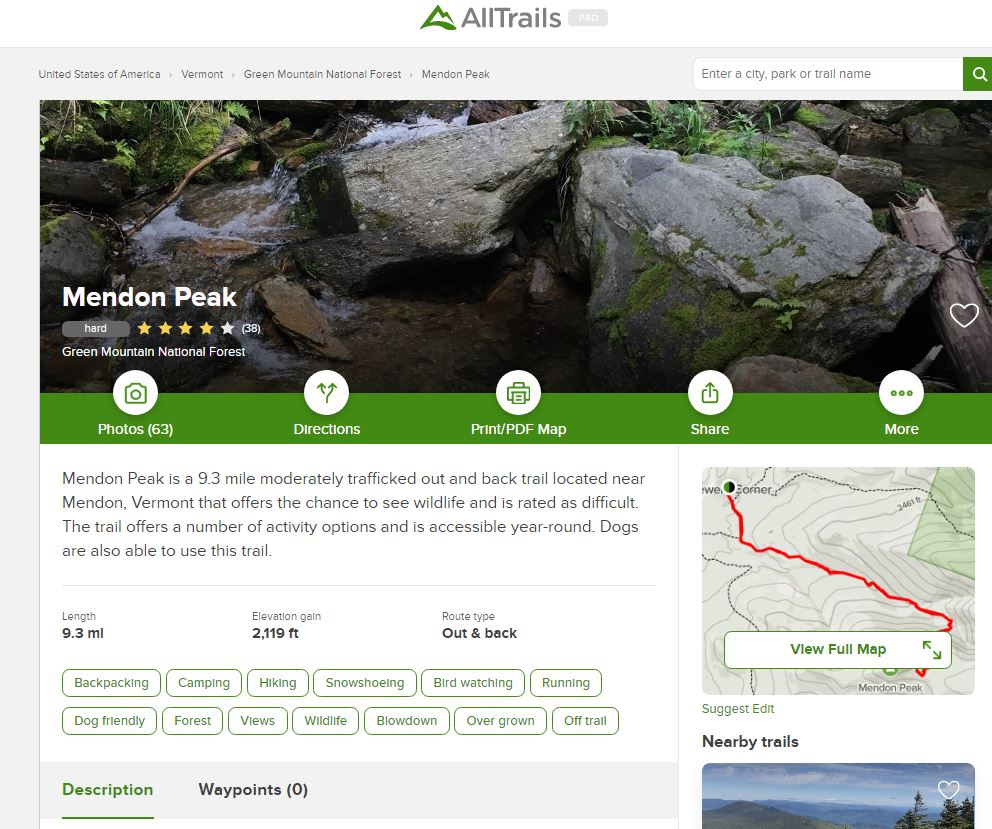

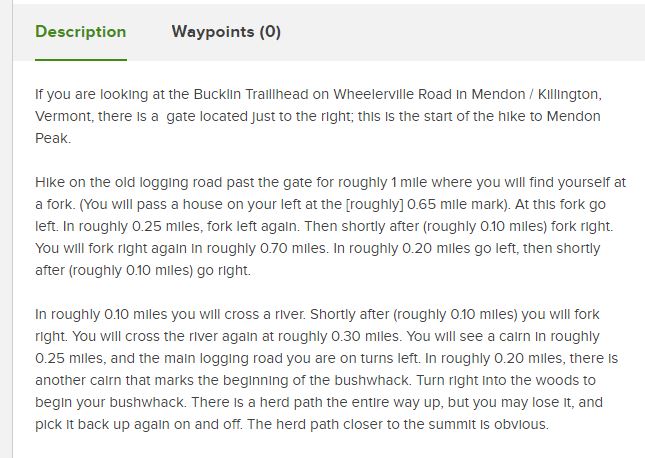

Apparently an AllTrails user posted a “hike” that described the herd path to Mendon Peak as “a moderately trafficked out and back trail” and the description and route were being utilized by people who did not know it was really a moderately trafficked herd path a.k.a former bushwhack turned into trail by the weight of pop-culture peaking bagging (and do compare “path” and “trail” in the dictionary when you have a moment). "Shame on whoever runs that site," the commentary began, “They are leading unprepared people into the wilderness with false information.” And then the usual pile-on about AllTrails began: “I would never, ever use AllTrails”, “garbage,” “wrong,” “I am glad you are spreading the word about AllTrails,” and (from the obligatory purist’s point of view) “Following someone else’s digital breadcrumbs goes against the spirit of the NEHH list regardless of how accurate your app might be.” Just about anytime someone brings up AllTrails in hiking social media discourse, the semi-commercial (both free and $30/year Pro options) app/website gets more than its fair share of hate. To be fair to the haters, as a source of accurate hiking information, AllTrails (existing in both website and smartphone app form) has its flaws. AllTrails hiking information is crowdsourced: hikers report their hikes to AllTrails along with GPS tracks produced by the AllTrails app, and AllTrails then publishes them—with minimal review and no pro vetting. The introduction of each hike starts with a stock language format blurb intro into which variables (some of them multiple choice) are filled in by the person doing the posting. For instance: "Mount Agamenticus via Ring Trail is a 1.7 mile heavily trafficked loop trail located near Cape Neddick, Maine that features beautiful wild flowers and is rated moderate. The trail offers a number of activity options and is best used from April until October. . . " Next there’s a GPS generated map (with an underlying stock OSM data layer, also a crowdsource product), a personalized hike description (which often gets overlooked), a weather forecast bar, then a crowdsource review section where others can rate and comment on the hike and their experiences with it. The net result is very akin to what you get with other crowdsource information streams (Wikipedia!): from very accurate and detailed data written by reliable hikers, right through mediocre intel from well-intentioned dilletantes (usually offering too much or too little information), down to occasional gnarly misinformation on the shitstick end of the bell curve. The running commentary and feedback offer the same spectrum of quality and utility. Bad AllTrails intel includes bushwhacks and herd paths passed off as actual designated trails; trails on private property being advertised as public trails; the misnaming of trails, summits, and other geographic features; and lousy hike descriptions. The really bad stuff tends to not stick around forever—eventually it gets too many negative reviews or complaints and is pulled out, and even if it isn’t you can usually suss it out by reading the reviews. AllTrails also has formal processes for removing inappropriate or misleading trail intel. That said, a lot of crap does make its way through, and it sticks around long enough to piss off the “serious hikers” out there. The concerns aren’t without legitimacy: people will get lost or hurt, private property will be invaded (angering the landowners and ruining what might have been longstanding sanctioned local use), formerly quiet destinations will suddenly become more crowded. On the other hand, there’s a lot of griping and sniping that seems full of its own latent dysfunctionality: big-brotherism (you’ll get hurt if you don’t hike the way I hike), authoritative prerogative (these, not those, are the only correct sources of hiking information), hiking elitism (you either hike it this way or you’re not a legitimate hiker), and xenophobia/ nimbyism (I don’t want people ‘from away’ hiking on ‘my’ turf). Mostly, though, the criticism seems to originate in a misunderstanding of what AllTrails is. If you can handle throwing out the bathwater without dumping the baby, the app does have a certain unique utility. What is the utility of AllTrails?

Using AllTrails is a bit of an adventure, for sure: it’s like venturing into a strange place without a map or reliable guide and having to ask the locals or weirdo riffraff explorers how to get from point A to point B. Some of them know what they’re talking about, and some don’t. Some can draw you a really good map on a napkin, and some will hand you a crap map that looks like a cartographer drafted it up. The more obscure the destination, the less numerous and helpful these people are going to be and the more uncertain your experience will be. You have to gather that intel and then use your own wits to make good decisions about where to go, how to go, and whose intel to trust. . .if you have no wits perhaps you’ll discover some through it. Think about that and let it sink in a moment: You have to gather that intel and then use your own wits to make good decisions about where to go, how to go, and whose intel to trust. The criticisms of using uncertain data of your choice to support your individual sense of adventure feel a little hollow, even controlling, when thought of in that light. Not being able to tell the difference between good and poor trail intel may say more about your own lack of hiking experience or your intolerance for uncertainty than it says about the value of the information itself.

There is also a special-flower kind of turf hypocrisy that plays out in knee-jerk social media criticisms of AllTrails. In comparing relative samples of advice and information supplied by members of Facebook hiking groups vs. crowdsource hikes posted on AllTrails, I don’t see a significant difference in good intel vs. bad intel (I prepped for this by reviewing a sampling of 30 high-response-volume Facebook posts and 30 random hikes posted on AllTrails, to arrive at nominal statistical legitimacy). So, if Facebook hiking forums are themselves crowdsource mosh pits (I dare you to disagree on that point—no disrespect to the hard-working moderators) why is it OK to be a member and participant there whilst shaming the consumption of AllTrails? Perhaps the commercial nature of AllTrails offends against the backdrop of its unvettedness? But AllTrails does donate 1 percent of its profits specifically to trail charities while (last time I checked) Facebook just enriches Mark Zuckerburg (does Zuck donate to trail charities? I have no idea). If it is not the commercialism of AllTrails that is odiferous, then is it that one can exude more control and authoritativeness in the context of a social media hiking forum among one’s known peers—vs. the authority-levelling peanut’s gallery of an AllTrails hike comment board? If it is not commercialism or the unavailability of ego-steroids, just what is it that is so hateful about AllTrails?

If you wanted to find out where to hike or how to hike, you either asked someone, read about it in a book you bought or borrowed, joined a formal hiking group (like the AMC, GMC, or ADK), or learned the hard way (guilty—my first White Mountains hike was Huntington Ravine, in a denim jacket emblazoned with a Jethro Tull album cover). You were fortunate if you were accidentally exposed to hiking—fitness consciousness was only just becoming a thing, and “getting back to nature” was still the province of hippies. If you were really serious and geeky about it (as was I), you spent hours pouring over topographic maps imagining what peaks were good places to hike and which ones would be duds. The thing is, we are really doing those same things these days, we’re just doing them a lot faster, often sharing in real-time and parsing data in much larger quantities. People still solicit advice from other hikers (now on social media and apps like AllTrails). People still give good advice and bad advice. People still read curated information, and curated information is still distributed and consumed in large quantities (AMC guides are distributed by Amazon and sell well pretty well there). People still participate in group hikes (witness the proliferation of Meetup). People still learn the hard way (by picking the lowest hanging source of information, lacing up a pair of shoes, and making a go of it). All of these methods are legitimate sources of learning how to hike, and, to some extent, unless we’re either extremely risk-adverse or extremely counter-dependent, we’ll use all of them at some point (even if we don’t admit it or are unaware we’re doing it). The kicker is that there are a heck of a lot more of us doing it. It’s crowded and hard to find a parking spot—and that rubbing of elbows constantly chafes on a subconscious level. If the number of fools in any given population is consistent across time (and why wouldn’t it be) that means that there are more fools on the trails now vs. 30 years ago but not more in proportion to the whole (you can test this theory by going back and looking at hiking accident reports from previous decades—trust me, we don’t have the market cornered on idiocy here in the 21st century). And it shows—fools do tend to make bigger headlines. They tend to trigger “serious hikers” more than ticks, blisters, or crotch-chaffing. Fools tend to leave bigger messes, and those messes are more obvious and impactful in the linear world of trails. Fools are more likely to need rescue. Fools take up space in parking lots, space on trails, space in campsites. They invade your space, waste your time, ruin your hiking zen, blast music while they hike, ask asinine questions, take selfies doing stupid things, and give you a big thumbs up while they “crush it.” And yet the sun shines on them equally, and the public open space is dedicated no less to them than to the trail-wise among us.

My supporting of hiking clubs and hiking groups, my pursuit of hiking lists and the creation of more lists, my peakbagging, my FKT, my adventure tourism, my nature loving, my tales of bears, my posting of hiking pictures with big thumbs up, my “crushing it”, my pole canopies, my support for the hiking gear industry (a lot of gear I can honestly hike without and not die), my support for making that gear into a fashion statement (and transforming the filthy exertion of hiking into a cool kid’s activity). My looking and sounding cool, wise, and authoritative on hiking forums and among other hikers. If hiking weren't a thing, AllTrails would wither on the vine. AllTrails exists because hiking is a popular thing, and hiking is a popular thing in part because I exist and call myself a hiker. The failings of AllTrails don't exist in a vacuum and aren't the real source of the hiking angst that wells up from my Freudian hiker-id-shadow when I bump into crappy hiking intel and behavior. I am. You are. We all are. --Paul-William Full disclosure: As a person who collects maps and hiking guide books as if they’re religious relicts, and is an admitted hiking geek and walking encyclopedia on hiking in the northeast United States and parts of Canada, I routinely use AllTrails as another source of hiking intelligence. Sometimes that intel is useful, sometimes it isn’t, but I’m glad to have it as a resource and will continue to unashamedly make high use of it, just as I make high use of the curated data. One doesn’t throw away a trove of data because one piece of it is proven inaccurate—that would be just as illogical as trusting all data unquestioningly.

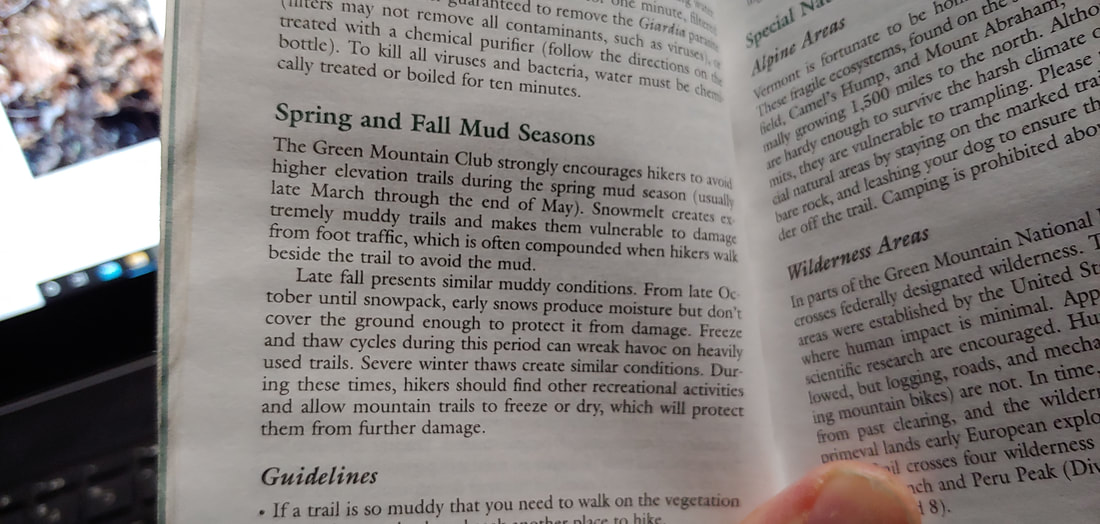

Vermont’s Green Mountain Club, which manages the famous 272-mile Long Trail (the first long distance hiking trail in the United States, which inspired the Appalachian Trail and other long distance trails), routinely closes the Long Trail and other high-elevation side trails during Mud Season. The closure lasts from late March through Memorial Day even though actual “Mud Season” conditions are not necessarily uniform throughout the trail system. During the closure, hikers are strongly encouraged to pursue other activities or hike lower elevation terrain where the ground has had a chance to dry out sooner. Generally speaking, most hikers in Vermont respect this—some out of a sense of personal responsibility, some falling into line through raw peer pressure. But Mud Season isn't unique to Vermont--it's an issue throughout the Northeast (for instance NY and NH) and other northerly latitudes. Changing how you hike in Mud Season is important. Trails are particularly vulnerable to destruction when the soil is saturated and 24-hour day/night spring freeze-thaw cycles are taking place. Wet trails churned up by a lot of boot traffic and frost heaves will erode quickly during the next heavy spring rain or warm-day melt-off, which means that trail maintainers (perpetually overworked, underfunded, underpaid, and with a backlog of priority trail work already on their slate), have to work a lot harder to shore up degraded trails. Hiking during Mud Season can also cause significant ecological damage—this is particularly true with regard to the fragile, endangered alpine plant communities above treeline. Too, Mud Season conditions influence hikers to use the trails in ways that exacerbate trail entropy. Spring ice “monorails” (caused by hikers compacting snow into very hard ice over the course of the winter hiking season) melt slower than the surrounding snowpack, keeping trail soils damp longer, and creating unpleasant slippery obstacles. Monorails also increase the speed of runoff and channel water flow along the sides of trails, gullying them. To avoid slipping on the monorail (especially on the downhill) and to avoid stepping in the muddy areas that have melted out around the monorail, some hikers (too many!) will walk off trail, which causes a widening of the trail course called “trail braiding.” Braided trails move the footway away from the true trail and whatever erosion control measures (water bars, steps, etc.) were built into it. This results in more erosion and can make it harder for hikers to identify the correct trail course during snow-off conditions, exacerbating the problem. The best way to avoid damaging trails in mud season is to refrain from hiking them until they have sufficiently dried out, i.e. hike elsewhere, at lower elevations, or further south, or engage in other activities altogether. Whether a trail is sufficiently dried out can be subjective and hard to assess if you don’t have experience with trail maintenance (and that’s why the Green Mountain Club has a general “closure” season). In places other than Vermont, one might consider a general rule of thumb: when the snowpack surrounding the trail is more than 40% melted out over any course of 500 feet in length; when there is a lot of lingering monorail with melted-out bare earth surrounding it; when the mud on the trail is ankle-deep or deeper for extended stretches; when you are finding yourself frequently walking around the trail to avoid ice and mud instead of on it—you’re probably hiking in “Mud Season.” If you are determined to hike in the early spring (perhaps you’re Gridding and are reluctant to give up the month of April), there are some things you can do to reduce your impact:

See you in the spring! --Paul-William

I ignored the advice, through- hiked the A.T. end-to-end and the leg was fine-- in fact, it was made a lot stronger by the experience. But the knee still troubles me from time to time. It's been a bit of a rollercoaster: some years I don't seem to have much trouble with it, other years I do. Going on thirty years of vigorous hiking since the initial injury, It's held out far better than I'd expected. The injury has changed my hiking over the years: it has slowed me down a bit on the downhill and flats, made me more careful of how I walk, and make me reasonable about the miles (I rarely will do a hike of more than 16 miles in a day). I have also taken up barefoot hiking (long story; fodder for a separate post) which has taken some stress off the knee during hikes (one must step more gently on the downhill when shoeless, which reduces wear and tear on the connective tissue).

My left knee looks different than my right knee: it is thick with internal scar tissue and musculature which, I imagine, have insulated and buffered it, not unlike how a tree will grow gnarly around an old wound. I imagine that my careful hiking practices and regular strengthening have extended the life of my knee beyond the threatened diagnosis (every doctor that looks at it reminds me what a mess it is). I have not yet submitted to the knife. I rarely wear a brace and I use just one wooden hiking stick for support. But it would be foolish to imagine that knee replacement surgery is not in my future.

The easiest and most common conclusion to that question, post-recovery, is bragging: I survived such-and-such, I’m a such-and-such badass, look at my badassery and tremble. Not to demean the value of celebration or the power of positive thinking, but if that’s your only tack and reward you’ll find plenty of back-pats on social media to help prop it up—you won’t even need to do it yourself; others will be glad to inflate your ego for you and help you dismiss your mortality. Ego-props as an end-goal are cheap prizes, however. It’s like hiking partway up a mountain and turning back, not because the weather is evil and I can’t reasonably go the rest of the way but because I am lacking in a fundamental kind of ummph that has nothing to do with hiking ability or trail conditions. It means I was never forced (or never conceded) to move beyond the denial stage (I’m not subject to the Law of Entropy the way other people are) or the anger stage (I “beat” my injury) before I was fortunate enough to recover. In his book Who Dies? the late Stephen Levine, famous for his series of books on conscious suffering and dying, asks the reader to imagine they are terminally ill, unable to care for themselves in the most basic of ways. Levine poses a series of questions: [paraphrasing here] when you are no longer able to do the things that most defined you, and others have to take care of your most basic needs (on the extreme end: buying your groceries, rolling you around in a wheelchair, bathing you, wiping your ass) what are you? who are you? where is that “I” that you were in previous years: the father, the attorney, the bicyclist, the carpenter, the doctor, the mother, the caregiver, the football player, the rock-climber, the skier. . .the hiker? Along those lines you may ask yourself: Who am “I” when my days of obsessively and relentlessly hiking Ultras and Grids and Redlines are officially over? Who am I when hiking a 4,000-footer is out of reach? Who am I when I can no longer easily walk down a flight of stairs? This line of questioning automatically awakens my old friend Despair—maybe he (or she) is a friend of some of you, too. A few years back I impaled my leg on a sharp tree branch while on a long hike through the Mahoosuc Range (a side bushwhack up the now-appropriately-named “Trident” peak); little bits of wood were imbeded deep in the wound; the wound became infected and I went in for surgery. I thought: what if they can’t fix this? What if I lose my leg? Can I live with that? I won’t sugarcoat it for you: a little, dark piece of the hiker in me was quietly engaging suicide scenarios even before I went in for surgery. I’m not mentioning this to set the stage for judging that kind of thinking. The beloved and brilliant White Mountains author Guy Waterman, who suffered debilitating (albeit hidden), lifelong mental health issues, ended his life by committing intentional hypothermia on Franconia Ridge—for a hiker, quite a way to go out. I cannot know his suffering and so cannot judge it or the outcome he chose. I can only use it as a mirror as I observe my own thoughts during the times I’ve had to question the continued existence of my identity in the face of a contrary or unacceptable reality. Any forced change in one’s self-identification is itself a kind of death. In preparing for "death" the mind grapples with the stages of coping with loss: denial, anger, bargaining, grief, and acceptance. Some of us move through those stages more easily than others; some get stuck. If I can no longer hike big mountains, but can still hike, the “big mountain hiker” must die to make room for a different kind of hiking identity. If I can’t hike anymore but can swim, kayak, bicycle, whatever, then the hiker must die and make room for those new identities. There is a loss and grieving inherent in that even if you work hard at burying the emotional labor—don’t let anyone tell you different. But beyond the endless morphing of identities lies the deeper question: what is this “I” that I keep creating? Is it important? How? When I strip it away, what is beneath it? In terms of hiking, one can ask more focused questions: what exactly IS a hiker? What does it really mean to be a hiker--beyond mere goal-posting and exploration? What is the kernel of that identity—and does it really even exist? I don’t have answers to these questions (and all answers will likely be subjective and privately individual) but I do think it’s important to ask them sooner than later. In some aboriginal cultures there is a practice of “preparing for death” which begins at a young age and continues until the end of biological life. The process, which involves song, vision quests, prayer, and other practices, is really a delving into the question of self-identity and what lies beyond it. As I understand it, if it is done well it can prepare the mind for the “little deaths” of identity that occur throughout life: changes in occupation or role, loss of loved ones, tribal warfare, change of physical ability and mental acuity. And in modern life in America, also divorce, unemployment, foreclosure, empty nests, pet death, failed business ventures, stock market crashes, hospitalizations, breakups, house fires, car accidents. . .and hiking injuries. If I can muster the courage to step beyond the props of the ego, the most important question might not be "when will I recover and hike again?" but "when the hiker can no longer hike [eventually, whether temporarily or more lastingly], what is left? Exactly who is this 'hiker' I have come to imagine I am?" Thanks to those who submitted photos and stories of their injuries. [Photo credits, by name in caption]. Postscript: my recent knee diagnosis is “badly contused ligaments/tendons /patella.” I consider it a deferment. |

TOPICS

All

Humor (The Parsnip)

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed